NEW AGENTS, NEW TARGETS: How Recently Approved Biologics Are Shifting the Pendulum of Care in Psoriatic Arthritis

In the last decade, there have been seismic changes in management strategies and pharmacologic options for treating patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Early therapy and tight disease control have emerged as key treatment concepts, while the range of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has rapidly expanded. Several drug classes now target distinct autoimmune and inflammatory pathways, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins (ILs), Janus kinase (JAK), T cells, and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE 4).1-4 Recently approved non-TNF inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in patients with PsA naïve to TNF inhibitor therapy as well as in those who have had prior TNF inhibitor treatment. Consequently, treatment for patients with more aggressive PsA is beginning to shift toward use of biologic therapies as first- and second-line options instead of conventional DMARDs such as methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine, and leflunomide.

The inflammatory process of PsA is heterogeneous and involves a spectrum of symptoms. These vary from arthritis in distal interphalangeal joints to, more rarely, arthritis mutilans, which is characterized by telescoping and flail digits. The clinical features of PsA can present as peripheral disease, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, or skin and nail disease, or they may be heterogenous among these domains.5 The clinical pattern of disease can also change over time.

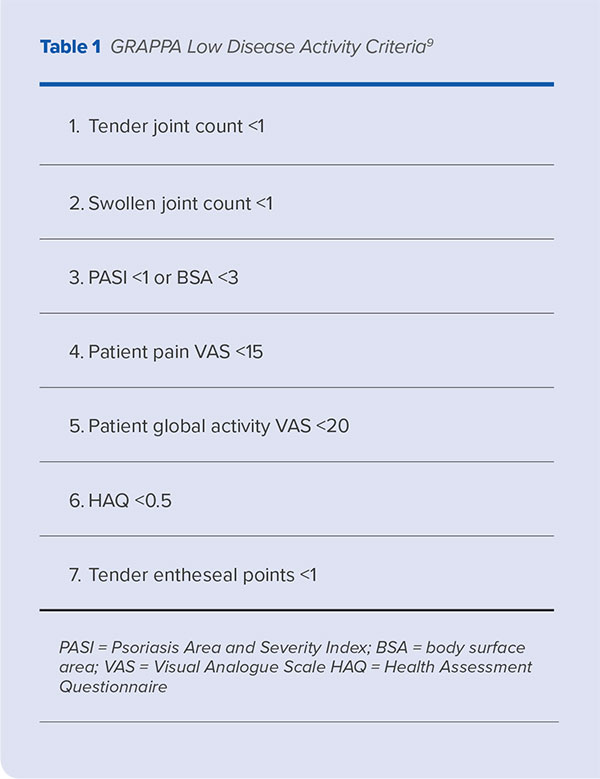

PsA is associated with several severe comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and depression, and patients with PsA may experience considerable psychological distress and reduced quality of life.6,7 Therefore, the goals of therapy are to achieve remission, optimize functional status, prevent structural joint damage, avoid or minimize complications, and achieve minimal disease activity, which is defined by clinically significant improvement in five of seven response measures or domains (Table 1).8-11 The domain with the most severe symptoms typically guides treatment, although many biologic therapies are effective in treating disease manifestations across clinical domains.

Current Guideline Recommendations

Two international evidence- and consensus-based guidelines authored by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) are available to help guide the treatment of PsA.11-13 Both guidelines recommend the use of biologic therapies in patients who require rapid control of skin and joint symptoms, as well as those who have not responded to non-biologic DMARDs after 3-6 months of treatment. These guidelines were updated in 2016 to include recently approved non-TNF inhibitor biologics and small molecules.

EULAR guidelines offer a graduated approach to the pharmacologic treatment of PsA, recommending non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as first-line treatment for patients with peripheral arthritis, followed by a conventional DMARD should this approach fail after 3-6 months. MTX is often the initial therapy used in PsA (unless patients have axial disease) despite limited clinical evidence concerning its efficacy in PsA.11,14 Among other commonly used conventional DMARDs, leflunomide is considered effective for peripheral arthritis but not for skin manifestations,15 while cyclosporine is effective for skin disease but less so for peripheral arthritis.16

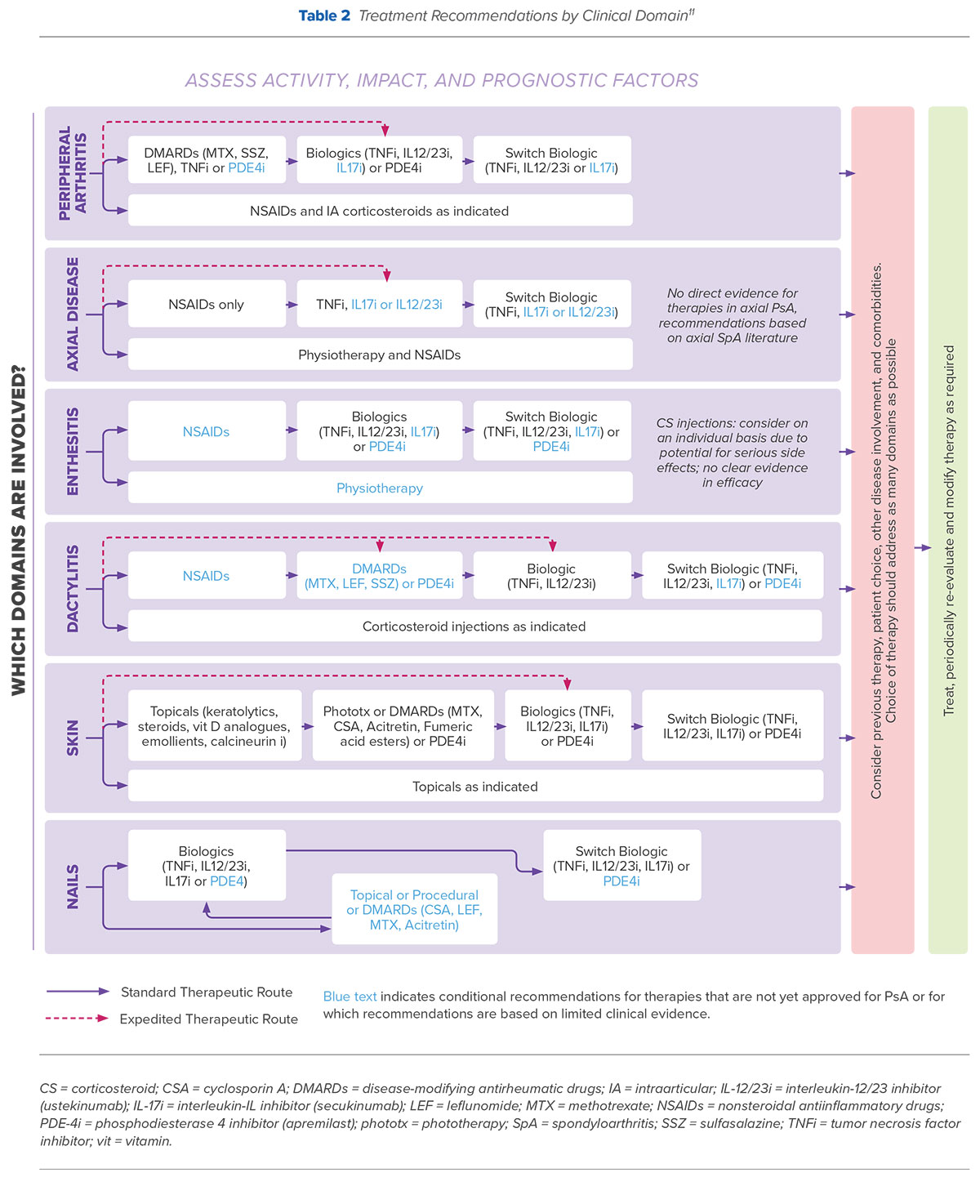

Both EULAR and GRAPPA guidelines recommend use of biologic agents for patients with peripheral arthritis that is resistant or intolerant to NSAIDs or for patients with axial disease in whom conventional DMARD therapy has not proven to be effective. However, GRAPPA recommendations, which are based on the disease severity of each clinically involved domain of PsA, also include an option for expedited initiation of treatment with TNF inhibitors, IL-17 inhibitors, or IL-12/23 inhibitors in patients with axial disease (Table 2). Additionally, while EULAR guidelines recommend switching to a second TNF inhibitor in patients who have failed initial TNF inhibitor therapy, recent GRAPPA treatment recommendations support switching therapy to either an alternate TNF inhibitor or a therapy with a different mode of action.11

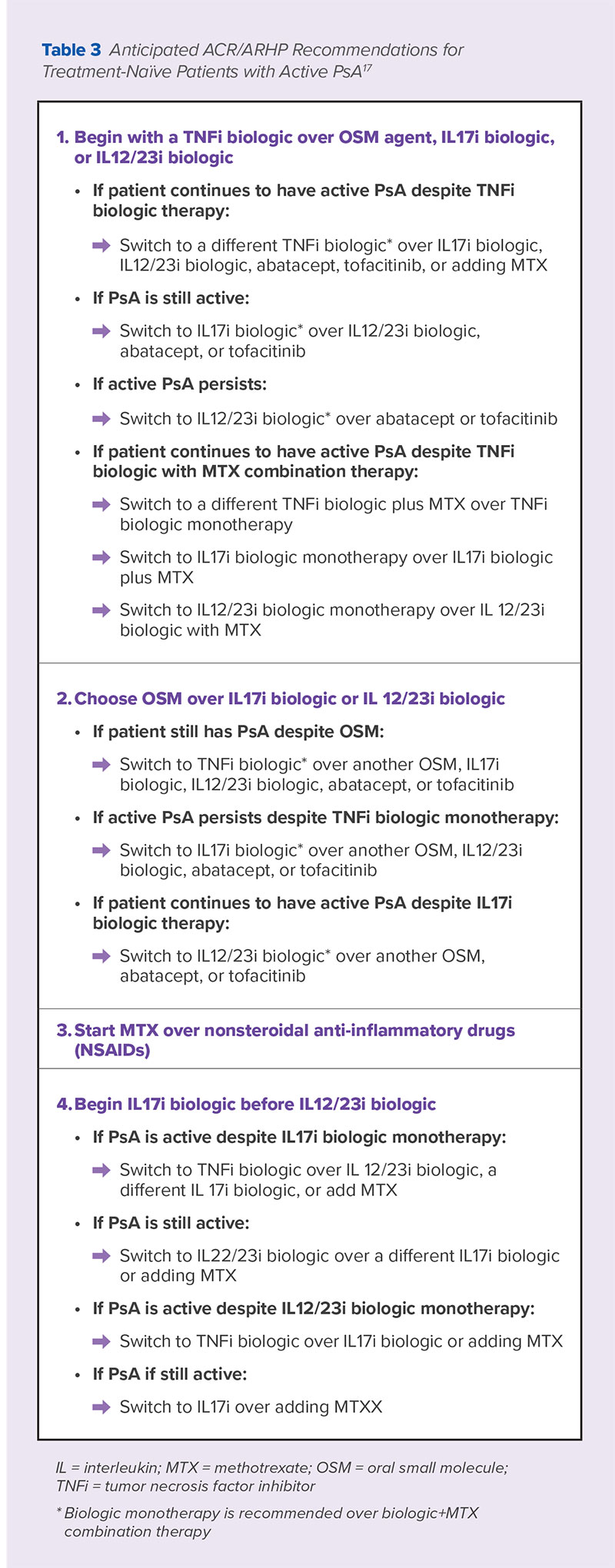

An update to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis based on a review of recent clinical evidence was previewed at the 2017 ACR/American Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Meeting in 2017. The full guidelines are expected to be published sometime later in 2018.17 A summary of the recommendations expected to be included in these guidelines are included in Table 3.

Early Treatment and the Concept of Tight Control

PsA outcomes are influenced by disease duration at treatment initiation.18 Delays in treatment can result in more erosions, sacroiliitis, and diminished quality of life, whereas treatment with a DMARD early in the course of PsA can lead to improved clinical outcomes and patient quality of life.19,20

In addition to early intervention, a treat-to-target approach has been proposed to improve joint outcomes in DMARD-naïve patients. A recent clinical study that randomized 206 patients with early, DMARD-naïve PsA to tight control (maximum dose DMARDs, including MTX monotherapy or combined with biologic therapies, with or without intra-articular and intramuscular steroids) or standard care reported greater improvement across a range of patient outcomes among the group treated with tight control, including quality of life, skin disease, pain, tender, and swollen joints, and cardiovascular biomarkers.21 In this study, if patients did not achieve minimal disease activity at any visit, treatment regimens were modified by increasing therapeutic dose, adding a new agent, or switching therapy. It should be noted that respiratory tract infection, nausea, fatigue, and gastrointestinal upset were commonly reported adverse events in the tight control group and may present barriers to patient acceptance in clinical practice.

Biologic and Other Therapies in PsA: Efficacy and Safety

TNF Inhibitors

TNF is central to the inflammatory response in PsA. Five TNF inhibitors are currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PsA; each has demonstrated comparable efficacy in treating skin and joint involvement as well as in preventing radiographic damage.22 Etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol are also approved for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and are considered effective for the treatment of spondylitis in patients with PsA. Overall, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients with PsA will respond to use of a TNF inhibitor, with little difference among available agents.23,24

Interleukins

In addition to other cytokines and immune modulators, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23 are over-expressed in patients with PsA. Ustekinumab is an interleukin monoclonal antibody that inhibits the activity of IL-12 and IL-23.25 Three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials involving patients with active PsA despite treatment with NSAIDs, DMARDs, or TNF inhibitors have shown that ustekinumab leads to ACR20 responses in a significant amount of patients with PsA, as well as significant improvement in skin disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and physical functioning.2,4,26 Ustekinumab is FDA-approved as monotherapy or in combination with MTX for adults with active PsA who have not responded to conventional DMARDs, and is effective for treating peripheral arthritis, sacroiliitis and spinal disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin psoriasis.2

IL-17 pro-inflammatory cytokines represent a second major interleukin target for biologic agents. Secukinumab is a fully human, high-affinity anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody that is approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with active PsA. Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials demonstrated higher achievement of ACR20 for patients with active PsA treated with secukinumab vs. placebo, as well as significant improvement in physical function as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI).26,27 The most recent phase 3 global clinical trial data for three different doses of secukinumab showed that a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved the primary endpoint (ACR20) with secukinumab vs. placebo in a dose-dependent fashion.28 Follow-up data affirmed these improvements, as well as in other clinical domains, including physical function and quality of life.29 Secukinumab is approved for adults with active PsA and is effective for treating peripheral arthritis, sacroiliitis and spinal disease, enthesitis, and dactylitis.

Ixekizumab is a humanized anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody that has shown efficacy in treating peripheral arthritis, sacroiliitis and spinal disease, enthesitis, and dactylitis in patients with PsA. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with PsA who are naïve to biologic DMARDs. In a randomized trial involving 417 patients with active PsA, treatment with ixekizumab 80 mg led to a higher rate of ACR20 achievement vs. placebo at week 24 (58% vs 30%), reduced radiographic progression, and improved psoriatic skin disease.30 A second randomized trial showed similar efficacy in patients with active PsA who were refractory or intolerant to TNF inhibitors, or experienced loss of efficacy.31

Oral Small Molecules

Apremilast is an oral PDE-4 inhibitor that mediates the breakdown of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in immune cells, resulting in decreased levels of proinflammatory cytokines responsible for the development of PsA. Apremilast was approved by the FDA in 2014 for the treatment of adults with active PsA and is considered effective for peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, nail involvement, and skin psoriasis.32 In clinical trials, apremilast demonstrated greater ACR20 improvement than placebo in both treatment-naïve and conventional DMARD-experienced patients, as well as improvements in physical function and skin psoriasis severity.33 The onset of clinical response was rapid (at week 2 of treatment) and was sustained for up to 52 weeks.34,35 Apremilast has also demonstrated preliminary efficacy and safety in combination with other biologic therapies in a single center study,36 and, most recently, in a study of early treatment in DMARD-naïve PsA patients, demonstrated significant improvements in ACR20, ACR50, and psoriasis response vs. placebo.37

Janus Kinase (JAK) Pathway Inhibition

Tofacitinib blocks the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that are regulated by the JAK- signal transducer and activator of the JAK-STAT transcription pathway, which leads to the down regulation of TNF and IL-17. In clinical trials, tofacitinib demonstrated significant improvement in ACR20 response in both treatment-naïve and TNF-experienced patients with PsA. It is FDA-approved for patients with DMARD-resistant PsA and is considered effective for treating peripheral arthritis and skin psoriasis. Two clinicals trials have demonstrated the superior efficacy of tofacitinib compared with either placebo or adalimumab in patients who are naïve to a TNF inhibitor or have had an inadequate response to a TNF inhibitor.38,39

Co-Stimulatory Blockade

Abatacept is a recombinant human fusion protein in which CTLA4 is fused to the IgFc region.40 This selective T-cell co-stimulation modulator was FDA-approved for adults with PsA in 2017. In clinical trials, abatacept increased ACR20 responses in patients with active PsA and an inadequate response or intolerance to nonbiologic DMARDs vs. placebo (39.4% vs 22.3%; P<0.001).41 The benefit on psoriasis lesions was more modest.

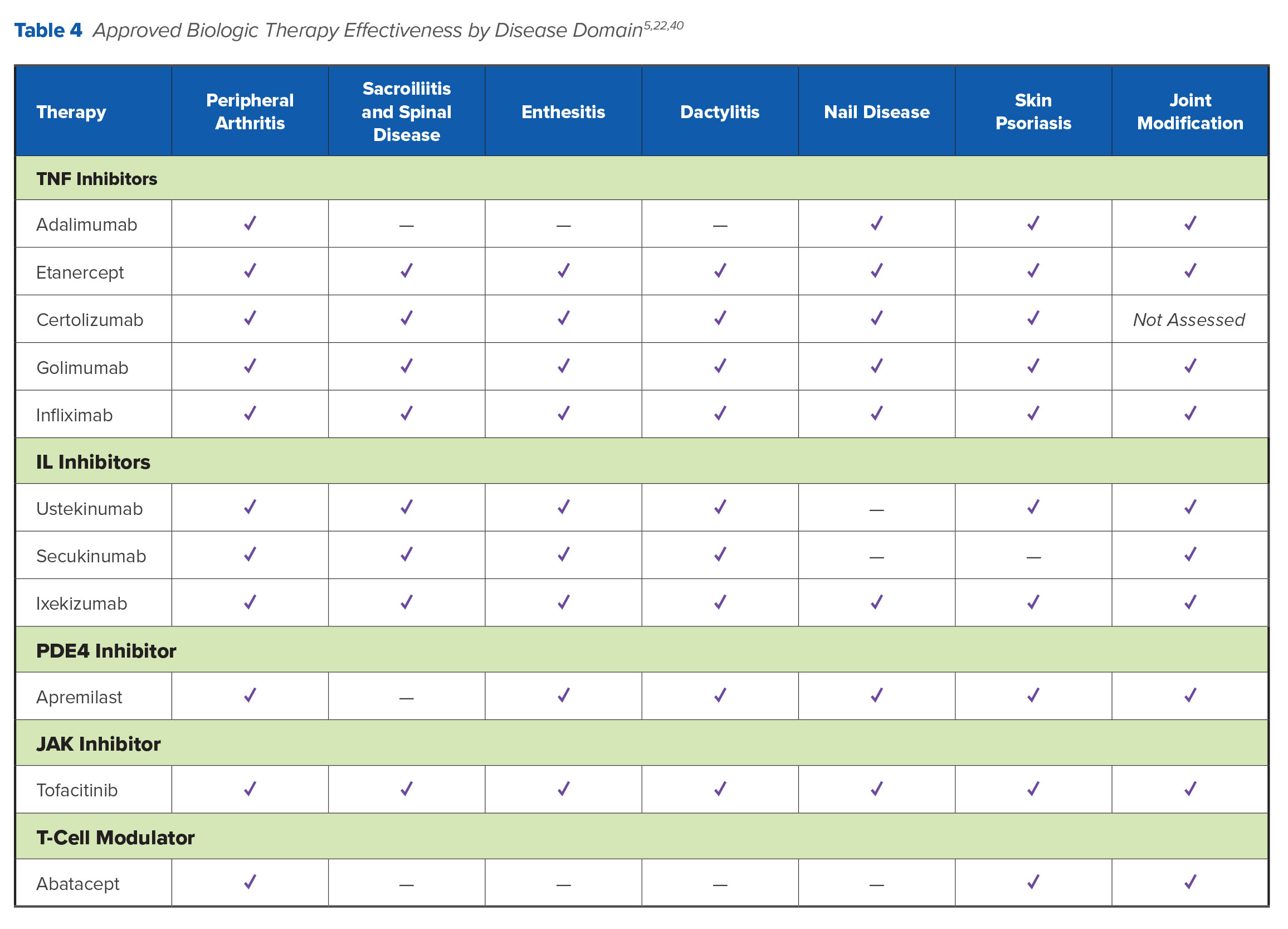

Table 4 summarizes therapeutic effectiveness by disease domain.

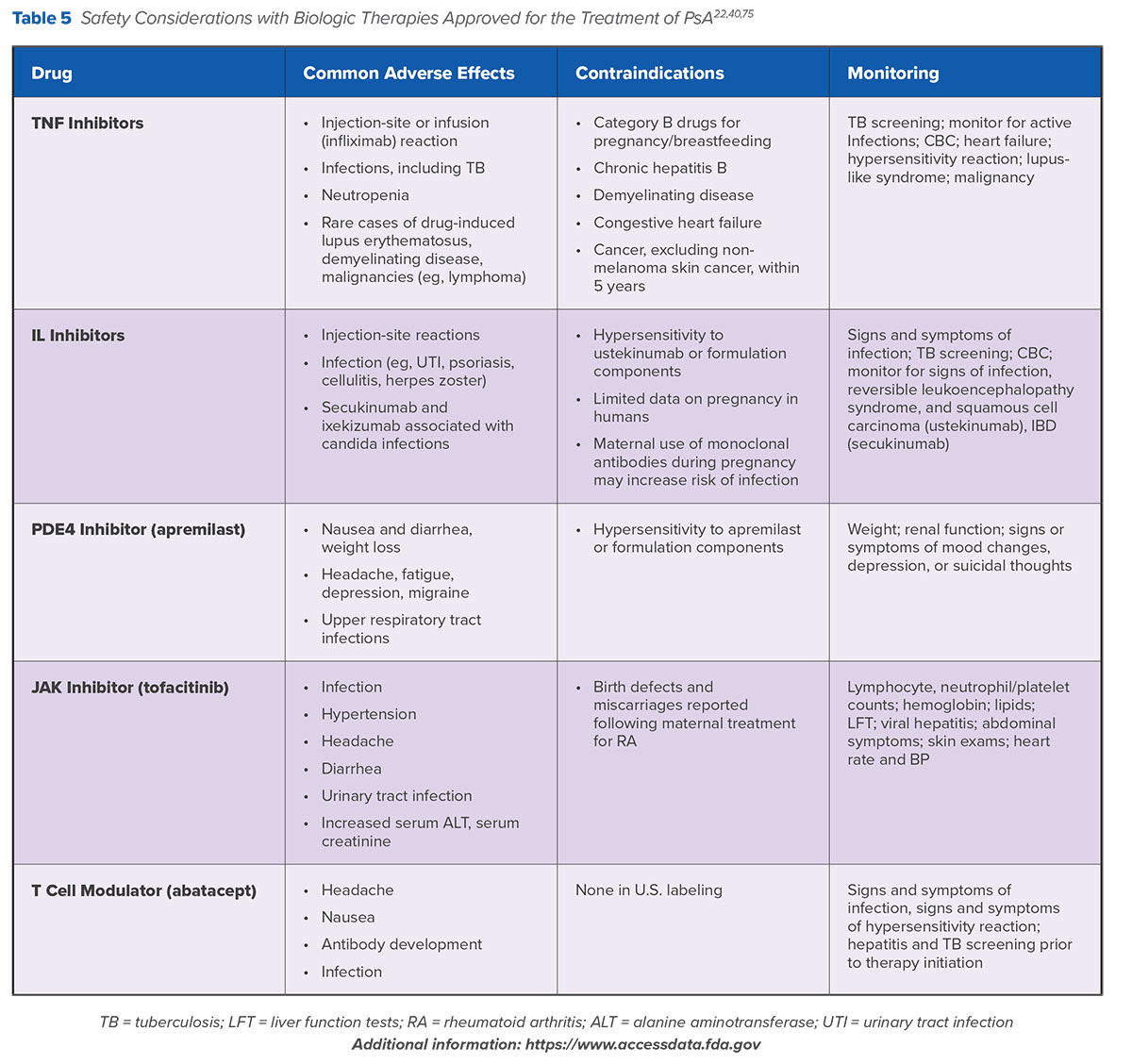

Safety Concerns with Currently Approved Biologic and Other Therapies

TNF inhibitors are associated with a wide spectrum of hematologic and metabolic adverse events, including opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis, cytopenias, lymphoma, heart failure, and hepatotoxicity. In some cases, TNF inhibitors can also aggravate skin lesions. Injection-side reactions, or, in the case of infliximab, infusion-site reactions, are also common. Adverse events lead to drug discontinuation in 7-11% of patients treated with TNF inhibitors in clinical trials, and real-world survey data suggest that as many as 45% of patients with PsA are dissatisfied with TNF inhibitor treatment.14,42,43 A meta-analysis of patient data from 74 randomized controlled trials (n=22,904) also found that the risk for non-melanoma skin cancer was twice as high in patients treated with TNF inhibitors vs. controls; it is unclear whether the use of TNF inhibitors increases the risk of melanoma.44 Contraindications to TNF inhibitors include advanced congestive heart failure, systemic lupus erythematosus, demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis, and other autoimmune diseases.

Adverse effects associated with interleukins include injection-site reactions and upper respiratory tract infections. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus, demyelinating disease, and opportunistic or serious infections such as tuberculosis and malignancies (eg, lymphoma) have been less commonly reported. Candida infections have also been reported in 1.7% of PsA patients treated with secukinumab and 3.3% with ixekinumab,45 as have a small number of cancers.4,26,31 Patients treated with an IL-targeted agent should be monitored for fungal infection and, if necessary, treated with topical antifungal medication.45

Common adverse events associated with apremilast in clinical trials include tension headache, headache, and migraine; fatigue; diarrhea and nausea; weight loss; and upper respiratory infections. Depression and, rarely, suicidal ideation have also been reported. Clinicians should use caution when using apremilast in patients with a history of depression and regularly monitor patient weight.

Headache is also a commonly reported side effect for abatacept, along with nasopharyngitis, nausea, and infections, including serious infections such as tuberculosis and sepsis.41 As with other biologic therapies, a small number of neoplasms have also been observed.41

Adverse effects associated with tofacitinib include infection rates that compare with TNF inhibitors, as well as hypertension, diarrhea, and headache. In clinical trials, the rate of adverse events was higher among patients treated with tofacitinib than placebo and included lipid abnormalities, liver enzyme elevations, and serious infections, including herpes zoster.39 Neoplasms have also been reported in safety data for tofacitinib,38 which contains a boxed warning about the increased risk for serious infections, lymphoma, and tuberculosis as well as the need for frequent monitoring.

Table 5 summarizes safety and monitoring considerations for biologic and small molecules used in the treatment of PsA.

Biologic Selection: First.Line Setting

TNF Inhibitors

As noted earlier in this issue, recommendations for PsA therapy are shifting toward the use of biologic agents as first-line options. However, EULAR and GRAPPA guidelines differ in which biologic agents they recommend in patients for whom NSAIDs or DMARDs are inappropriate. EULAR guidelines recommend TNF inhibitors for patients failing NSAIDs, while GRAPPA guidelines recommend TNF inhibitors as well as IL-17, IL-12/23, or PDE4 inhibitors but make no recommendations to establish hierarchy among agents. It should be noted that both of these guidelines were published prior to the approval of tofacitinib and abatacept, hence they are not included in the publications.

The available clinical evidence does provide some guidance for the selection of biologic therapy in first- and second-line settings. TNF inhibitors have demonstrated similar efficacy on different clinical subsets of PsA, including enthesitis, synovitis, dactylitis, and axial disease, as well as for skin and nail psoriatic lesions (Table 4). Given the comparability between TNF inhibitors, in clinical practice, drug selection is typically driven by factors such as cost, dosing frequency, route of administration, and payer requirements.5 However, many factors influence TNF inhibitor outcomes in PsA, including baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, concomitant MTX therapy, sex, and body mass index.46 The number and severity of comorbidities in patients with PsA is associated with poorer treatment response and shorter treatment duration compared with patients without comorbidities.46,47 Notably, patients with PsA have a higher incidence of cardiovascular (CV) disease compared with patients without PsA. While there are no studies that directly compare different TNF inhibitors in preventing CV or metabolic complications in patients with PsA, this drug class may reduce the frequency of CV events.48,49 TNF inhibitors may also be more appropriate for patients with anterior uveitis.49

Non-TNF Biologics

Both ustekinumab and secukinumab have demonstrated good efficacy for the treatment of skin disease, dactylitis, and enthesitis. Compared with TNF inhibitors, ustekinumab has shown better efficacy for the treatment of psoriasis but worse efficacy for peripheral arthritis. It may be considered a reasonable first-line option for PsA patients who predominantly present with skin disease (Table 4).50 Apremilast has shown efficacy in patients with both skin and joint involvement, although responses have been less frequent in clinical trials than those observed with other biologic agents. Apremilast has a favorable safety profile, does not require laboratory monitoring, and is associated with weight reduction in patients with obesity.51 Skin responses with abatacept have been inconsistent, with TNF-naïve patients showing better responses.41

There are, as yet, no head-to-head trials evaluating the comparative efficacy and safety of non-TNF biologics in patients with PsA. However, a 2018 systematic review and network meta-analysis assessing the comparative effectiveness of abatacept, apremilast, secukinumab, and ustekinumab reported no significant differences among these agents for efficacy and safety.52 Secukinumab 300 mg was ranked highest for ACR20 response rate and overall safety while ustekinumab 90 mg presented the lowest overall risk for serious adverse events.

Another 2018 meta-analysis similarly reported effectiveness for IL-17 and IL12/23 inhibitors used as monotherapy in patients with prior TNF exposure as well as patients who were treatment-naïve.53 In that meta-analysis, patients treated with IL inhibitors achieved the primary endpoint (the percentage of patients who reached ACR 20% by 24 weeks) at a significantly higher rate versus placebo. MTX combined with an IL inhibitor did not result in significantly increased benefit compared with IL inhibitor monotherapy. The meta-analysis also concluded that IL inhibitors are generally safe and well-tolerated, with no increase in the incidence of serious adverse events observed in the treatment vs. control groups (P=0.39). The incidence of overall adverse effects increased slightly in the treatment arms, but this was accompanied by lower withdrawals due to toxicity compared to placebo.53

Practical Pearls

GRAPPA guidelines include a treatment ladder with therapeutic options tailored to PsA clinical domains (Table 2). Treatment decisions should be individualized according to disease characteristics, patient preferences, and patient-related features (eg, age, sex, comorbidities, previous treatment).11,13 A patient’s predominant symptoms should be the primary drivers of therapy selection. For many patients with accompanying psoriasis, itch and pain may be the most troublesome symptoms, and skin clearance might be more important to them than joint improvement.54 Finally, although first-line biologic therapies may be warranted for some patients, especially if they have already been treated for psoriasis, insurance coverage and eligibility remain significant barriers.14,55 Clinicians can consider measuring disease activity in the core clinical domains to assess treatment effectiveness prior to therapy modification, but should be aware that expected improvement in joint symptoms is typically less than in skin symptoms.56

Considerations in Switching Biologic Therapy

Treatment Failure

Drug survival measures the time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy, including stopping or switching. The average drug survival time for TNF inhibitors in patients with PsA is less than 5 years, with etanercept reported as the TNF inhibitor with longest-lasting efficacy.57

A survey fielded by the National Psoriasis Foundation found that adverse effects, lack of effectiveness, and inadequate response are the main reasons that patients cite for therapy discontinuation,14 which occurs for at least half of PsA patients within 1-2 years of initiating treatment with TNF inhibitors.59,60 Analysis of data from the CORRONA Registry (n=1,241) showed that only 52% of patients continued with their TNF inhibitor for at least 24 months; the overall discontinuation rate was 46%.61 More biologic-naïve than biologic-experienced patients remained persistent with TNF inhibitor treatment, while biologic-naïve patients were persistent with treatment for longer (32 vs. 23 months). Shorter disease duration was associated with better persistence in both groups, and the risk of discontinuation was highest among biologic-experienced patients who had prior synthetic DMARD treatment and greater skin involvement.61

Switching to TNF Inhibitors

When treatment fails or is ineffective, guidelines developed when TNF inhibitors were the only available DMARDs recommended switching patients from one TNF inhibitor to another.11 Indeed, observational patient registry data (n=520) suggest that biologic cycling—switching to another TNF inhibitor when the previous one fails—has become increasingly common among dermatologists and rheumatologists.62 Analysis of claims data found that 1 year following biologic initiation, 22.9% of PsA patients (n=1,235) had switched to a different biologic (most commonly another TNF inhibitor), 26.8% had discontinued therapy without switching or restarting, and 5.8% discontinued and restarted the index biologic.63 However, prolonged exposure to one TNF inhibitor is a factor in response to subsequent TNF inhibitor treatment.4,64-68 Patients who switch to a second TNF inhibitor following first-line TNF failure are likely to have a poorer response compared with patients who do not switch, and drug survival for the second TNF inhibitor is likely to be shorter than for the first.56,58 Only infliximab efficacy appears to be independent of prior TNF treatment.56

Switching to Non-TNF Inhibitors

Although the available clinical data on outcomes associated with switching patients to biologic DMARDs with different mechanisms of action are limited, they potentiate a shift toward non-TNF inhibitor therapies as alternative agents when TNF inhibitors fail. Ustekinumab (IL-12/23 inhibitor) and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitor) have demonstrated greater responses in clinical trials compared with placebo for patients who failed to respond to more than one TNF inhibitor.4,28

This finding is also reflected in real-world data. Analysis of PSOLAR (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry) patient data found that ustekinumab had better drug survival in both biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients as second-line therapy compared to TNF inhibitors.69 Discontinuation was also lower for patients using ustekinumab than for TNF inhibitors at first line and beyond, and time to discontinuation of ustekinumab was longer compared with TNF inhibitors.69

Although data supporting the benefits of combining MTX with biologic DMARDs are mixed, MTX combined with etanercept is considered efficacious in selected patients for whom monotherapy with either agent is insufficient.70 Moreover, TNF inhibitors combined with MTX show longer therapy duration rates.71 Both apremilast and tofacitinib have demonstrated efficacy compared to placebo in patients with prior TNF inhibitor therapy.33,39 Given the availability of efficacy data in support of non-TNF inhibitors following TNF inhibitor failure, updated 2016 GRAPPA guidelines provide a conditional recommendation to switch PsA patients with previous exposure to a TNF inhibitor to a biologic DMARD with a different mechanism of action.11

Practical Pearl

Patient concerns with safety and the need for laboratory monitoring pose potential barriers to treatment initiation and continuation. Adverse events have led to drug discontinuation for 7-11% of patients in clinical trials, and real-world survey data suggest that as many as 45% of patients with PsA are dissatisfied with TNF inhibitors in particular.14,42,43 When considering a switch in biologic therapy, clinicians should be aware of contraindications and other safety issues. For instance, many biologic agents are associated with an increased risk for serious infections or, in some cases (ie, TNF inhibitors, ustekinumab) may worsen skin symptoms. TNF inhibitors are a viable option especially for patients with cardiovascular disease due to their beneficial effects on subclinical markers of inflammation and atherosclerosis (eg, C-reactive protein). There are limited data to indicate an association between biologic therapies and birth defects or adverse pregnancy outcomes; hence, TNF inhibitors may be used with caution in patients who are pregnant or considering pregnancy.

Insights From Real-World Clinical Practice Data

Undertreatment of PsA has been well-documented. For instance, biannual survey data from the National Psoriasis Foundation indicates that between 2003-2011, a majority of patients with PsA with concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis (77.8%) were receiving no treatment or only topical treatment for their pain symptoms.14 Among patients treated with any biologic therapy, etanercept and adalimumab—the first and second approved TNF inhibitors—were used most frequently. Similarly, the more recent Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic (MAPP) Arthritis Survey (n=1,206) reported that only 25% of PsA patients were being treated with biologic therapies,55 while analysis of claims data from a large commercial health plan (2004-2015) showed that of 9,222 patients with PsA, 57.2% initiated therapy with conventional DMARDs, while 42.8% did so with biologic DMARDs.72 MTX was the most frequently used DMARD (80.6%), while etanercept and adalimumab remain the most frequently used biologic agents (49.1% and 34.4%, respectively). Almost one third (31.1%) of conventional DMARD patients and 20.1% of biologic patients had their treatment regimen modified within 1 year of treatment initiation, with an increased likelihood of treatment modification over time. Patients were most likely to be switched to etanercept or adalimumab following MTX initiation, MTX was most commonly added following initiation of TNF inhibitors, etanercept was switched to adalimumab, and vice versa. Switching was more common following initiation of a synthetic DMARD.

More recent real-world observational data reflect a more complex picture of gradual, uneven change in the use of biologic therapies in clinical practice. For instance, analysis of CORRONA registry data (n=520) between 2004-2012 suggest that TNF inhibitor therapy is being initiated earlier in the disease course, although some physicians remain reluctant to initiate biologic monotherapy.62 In this analysis, the proportion of patients receiving TNF inhibitor monotherapy decreased over time, while the proportion starting combination therapy remained steady. At the same time, other studies suggest that although initiating therapy with conventional DMARDs remains a preferred first-line treatment approach in patients with PsA, clinicians are increasingly making therapy selections and relatively rapid modifications that reflect the emergence of newer therapies.59 For instance, recent analysis of CORRONA registry data showed that biologic-naïve patients with both psoriasis and comorbid PsA (40%) had been or were being treated with apremilast (40%), IL-17A inhibitors (44%), IL-12/23 inhibitors (32%), or TNF inhibitors (41%).73

Summary

New pharmacologic options for treating patients with PsA have led to updates from international guidelines and, imminently, new ACR recommendations. These updates emphasize a more prominent role for a wider range of biologic agents as first-line therapies, which are also candidates when considering therapy modifications should first-line therapy fail. Several other therapies are currently under investigation, such as interleukins bimekizumab (IL-17A and IL-17F inhibitor), guselkumab and, risankizumab (both IL-23 inhibitors).74 Novel targets and pathways are also in preclinical development for PsA, including nerve growth factor receptors, the mTOR signaling pathway, and angiogenesis.40 However, many barriers remain to effective PsA management, including patient concerns about safety , the need for ongoing laboratory monitoring, and cost or lack of insurance coverage. Clinicians now have a wider range of available therapies to counter some of these barriers and support decision-making that incorporates patient preferences and expectations.