TK was an 8-year-old female who presented to our pediatric rheumatology clinic about a year ago with a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test result (1:320), general fatigue, and a recent preliminary diagnosis of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) that was made after she was hospitalized with pneumonia. A review of TK’s medical history showed hemoglobin S sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited red blood cell disorder (both of her parents also had the disease), for which she received regular exchange transfusions via an implantable device.

The month prior to her pediatric SLE diagnosis at a local hospital, TK was hospitalized for several days with abdominal pain and joint pain in her wrists, knees, and feet without swelling. Her mother told us that, at the time, TK’s urine looked dark brown, but it had returned to normal coloration by the time she was again hospitalized a month later. Her clinicians concluded that the pain was most likely attributable to her SCD, although TK’s mother was dubious as she had not experienced joint pain throughout her own personal history of SCD.

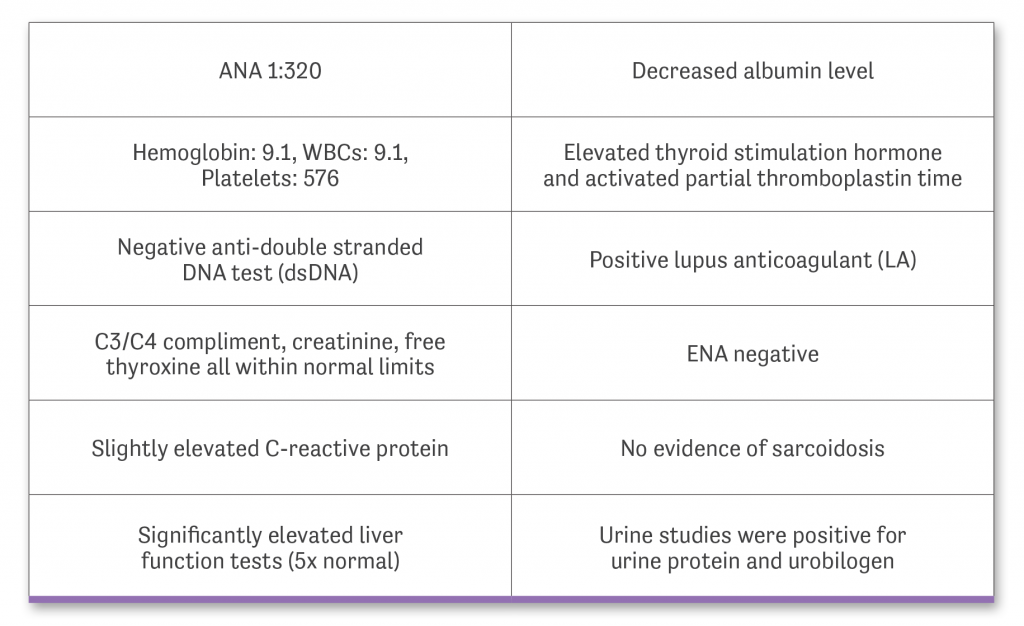

TK’s lab workup provided to us yielding the following results:

TK’s physical exam in our office was completely normal. We therefore interpreted her fatigue to be consistent with a child recovering from a severe case of pneumonia. TK complained of general intolerance to physical activity, though there was no shortness of breath or difficulty breathing.

Uveitis had already been ruled out by an ophthalmologist prior to TK coming to our office, which would otherwise have been a possible explanation for her abnormal ANA result. ANA results can also be abnormal in children who are ill, so we decided to repeat the test, as well as get a urinalysis, now that TK’s influenza and pneumonia had passed. Our office is diligent about ordering urine testing in new patients since children are often at high risk of developing autoimmune diseases that affect their kidneys such as lupus nephritis or Wegener’s granulomatosis. TK’s mother chose to have her blood drawn during her next exchange transfusion the following week rather than in our hospital.

It was almost two weeks later that we finally received the results of the repeat ANA and urinalysis. Much to our surprise, TK’s ANA result had ballooned to 1:>10,240 and she had protein with 3+ glucose in her urine. We immediately contacted TK’s mother to inform her of these abnormal lab results and to urge her to bring TK back to our office as soon as possible for further evaluation.

Our first step was to expand our urine testing to include a urinalysis as well as urine protein and urine creatinine tests so that we could calculate TK’s urine protein creatinine (UPC) ratio. UPC results give us an idea of how well a patient’s kidneys are working. There are often changes in a patient’s UPC that show up before serum creatinine levels rise, making it helpful in identifying children at risk of renal disease.

Our urgency initially alarmed TK’s mother. Because we showed no initial reason for urgent intervention during our preliminary workup, her mother asked us to send all lab results to TK’s primary care physician (PCP) and hematologist so that they could determine the appropriate next steps. TK’s mother told us that her daughter was feeling fine and nothing had changed in her overall health since her last visit to our office. We did our best to explain to her that fluctuations in lab results are not unusual, but that the most recent results we had in hand were alarming and required urgent follow-up. She assured us that she “was on it.”

TK saw her PCP the following week to have the additional laboratory tests we had requested performed. Because her mother refused a separate additional blood draw, we had to wait until TK’s next exchange transfusion to get the information we needed. We had a strong suspicion that the initial diagnosis of SLE would be confirmed, but we could not rule out other possibilities without the missing lab tests.

Several weeks later, we found out that TK was recently also evaluated by a second pediatric rheumatology practice nearby. At this practice, TK was preliminarily diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, although TK’s mother eventually told us that she had not provided this practice with any of TK’s recent lab results and did not notify them of our alarm related to her high ANA levels.

After our initial consultations, TK popped back up onto our radar screen when our office was called to arrange her transfer from an outside hospital’s emergency department (ED) to our ED. She had been hospitalized the previous week with a 104.5-degree fever and because she generally “just was not feeling well.” Urine and blood cultures were negative, so TK was eventually discharged with a prescription for oseltamivir phosphate. Her mother had difficulty initially acquiring the medication, so TK didn’t start treatment for nearly a week after her discharge. The medication was initially effective, but within a week, TK was again febrile, complaining of a cough and neck pain that prompted a return visit to the outside hospital’s ED and, eventually, a transfer to our hospital’s ED.

Chest x-rays were performed that showed cardiomegaly and bilateral pleural effusions. Nothing abnormal was seen on ultrasound, although an echocardiogram showed a large global pericardial effusion with tamponade at the location where the right atrium was collapsing during systole.

TK was transferred to pediatric intensive care, where she was intubated and underwent pericardiocentesis to remove 500 ml of fluid. A drain was left in place. TK also received a 3-day course of high-dose methylprednisone 30 mg/kg before transitioning to hydroxychloroquine after extubation.

We again repeated lab testing and made a definitive diagnosis of SLE based on TK’s high ANA levels (1:>10,240), positive dsDNA and LA, positive anticardiolipin antibodies, proteinuria, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and arthritis. TK was discharged from the hospital with instructions to take hydroxychloroquine 100 mg po daily and prednisone 40 mg po daily.

We opted against initially starting TK on mycophenolate mofetil due to her non-functional spleen secondary to SCD as well as the risk of infection. Upon further discussion with TK’s hematologist, we agreed to start mycophenolate during our steroid taper.

It has now been 6 months since our last major adjustment to TK’s treatment. She is doing extremely well with no signs of disease flare. This latest scare seems to have jolted TK’s mother into action as she is now one of my “prize mothers,” following our every instruction, getting her daughter’s labs drawn on schedule, and engaging with our team in fruitful discussions about TK’s disease. She now realizes the “lion” this disease can be after seeing how close it came to devouring her child.

There are few routine SLE cases in the pediatric world. TK’s case was complicated by her young age at presentation (pediatric SLE typically presents between the ages of 12 and 14),3 her absence of typical flare symptoms, our difficulty obtaining lab results, and irregular follow-up visits to our office. Her initial care was extremely fragmented, with management at three different hospital systems that all prioritized different components to care.

With all of these complications, it’s hard to fault TK’s mother for being resistant to our initial recommendations. Her daughter appeared largely happy and healthy when we first saw her, and there was naturally some surprise when we urged immediate medical interventions based upon abnormal lab results. Putting myself in TK’s mother shoes as a non-healthcare provider, I would likely have been skeptical as well without discussing the matter with a clinician with whom I had some personal history (ie, her pediatrician).

This case serves as a good personal reminder of the need to communicate information in a delicate yet persistent fashion with our patients and their families. We never want to underemphasize the potential impact of a diagnosis like pediatric SLE, but it’s also important not to sound the alarm too quickly with a family that is fragile and does not know us well.

AUTHOR PROFILE:

AUTHOR PROFILE:

Cathy Patty-Resk, MSN, RN, CPNP-PC is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner in the Division of Rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Michigan in Detroit, MI, where she provides medical services to inpatient and outpatient pediatric rheumatology patients.

References

1. Sinha R, Raut S. Pediatric lupus nephritis: Management update. World J Nephrol. 2014;3(2):16-23.

2. Akikusa JD, Schneider R, Harvey EA, et al. Clinical features and outcome of pediatric Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):837-44.

3. Thakral A, Klein-Gitelman MS. An update on treatment and management of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(2):209-219.