Sometimes as rheumatology nurses, we walk into a room and our heart sinks as we’re faced with a patient who we know is going to challenge every nursing skill that we possess.

Other times, we brighten up as we see a patient who is like an old friend and has become an extension of our own family.

Then there are those patients who can set us back an hour by bringing in scores of articles and information to review together, whether it be wisdom from Dr. Oz or Dr. Google.

Wouldn’t it be great to know exactly what we are walking into when we open the door to every one of our patients? What if we gave every patient a 5-minute personality test that told us the best way to approach them and care for their needs? If we knew in advance what a patient desired, perhaps we could better meet those needs and make more efficient use of our time.

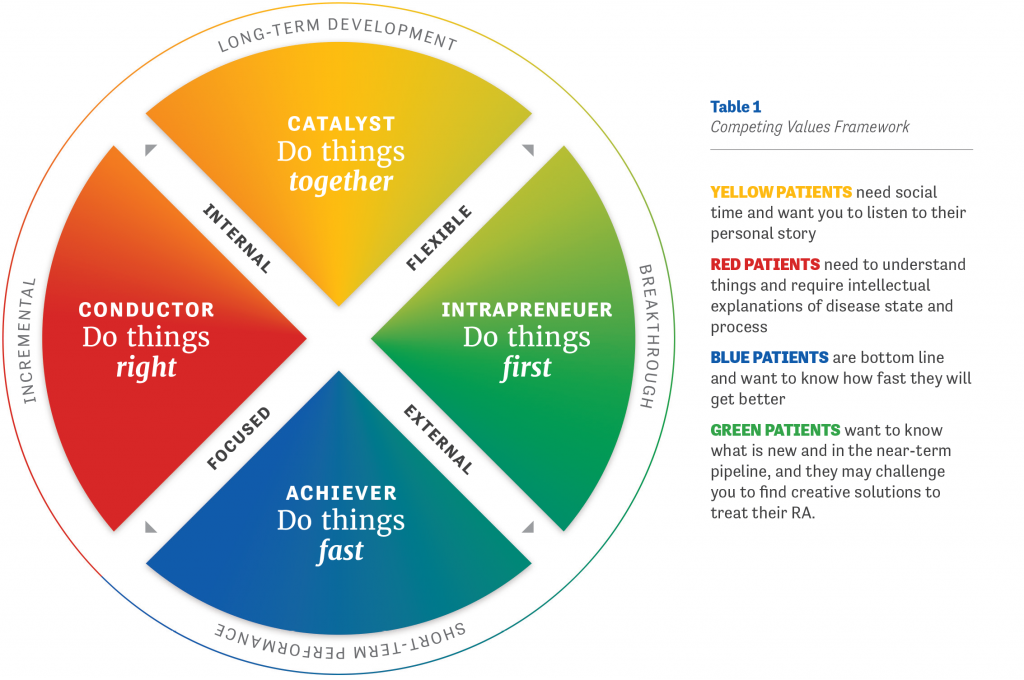

These tools certainly exist. One of my favorites is the Competing Values Framework that was developed at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business to help build work teams (Figure 1). This model identifies four personality types that are linked to specific colors.1 While not everyone fits into one clear personality type, many of us have dominant traits that can be grouped into specific quadrants.

Yellow people are social and community focused. They crave collaboration, social support, and a feeling of belonging. In our offices, yellow patients tend to be very social and chatty. These are the patients who might be best suited to be prescribed the same medication regimen as a friend or family member, or to meet other patients who are taking their same medication so that they can talk to them about how the drug made them feel. Yellow patients crave support and like to have someone that they can call and ask questions of. You might get a clue that your patient is yellow when you hear their life story and how their disease is impacting their social and family life.

Blue people are very bottom-line. They want results, and they want them fast. The blue patient will ask your opinion about the treatment being recommended for them, and they will likely expect it to work quickly so that they can get back to their usual daily regimen. They may want you to employ a quantitative measurement tool to concretely prove or disprove that their regimen is working. For blue patients, it’s our job to provide them with realistic timeframes of expected improvement from a specific treatment regimen. Blue patients can be difficult to deal with at times if they believe that things are not being done properly or fast enough.

Red people are the managers of the world. They are all about the process and gathering data to support the process. These are the patients who bring in folders of data and articles to review. Red patients need to discuss the importance of Treat to Target goals and be reassured that treatment will be adjusted or changed every 12 weeks (or less) if they have not met the goal of either remission or low disease activity.2 Red patients like structure and punctuality (don’t keep them in the waiting room too long!) and appreciate being provided with relevant resources to advance their knowledge base. They are the patients who will call the office in advance of their appointment to see if there are labs, tests, or forms they can fill out to ensure a more efficient visit.

Green people are our “idea” patients. They are the ones most likely to experiment with alternative treatments or have creative ideas about managing their RA. They like to be the first to get the newest and greatest gadget or technology. The green patient is willing to take risks on treatment regimens that perhaps don’t have a significant evidence base behind them to feel better fast. Green patients rapidly embrace change and adjustments to therapy, but they still need understanding and compassion when discussing how their disease impacts their lives.

Personally, I am mostly yellow and blue. I love the social connection I have with my patients and their families (that’s the yellow), but I am also deadline-oriented when I have a new idea or something needs to be done (that’s the blue).

As you are reading this, I’ll bet you are categorizing some of your more challenging patients and perhaps gaining a greater understanding of how and why they are the way they are. That’s what I did with one of my most challenging patients, DQ, who first came to me 3 years ago with joint pain. We quickly diagnosed him with RA.

DQ is both very red and very blue. He is bottom line and wants to get better fast, but he also wants to understand the process, the disease, and the outcomes to expect. At every visit, DQ seemed to take endless amounts of time talking through every aspect of his disease with me, what the long-term implications were, and what each step of treatment would include. He wanted to know about the mechanism of action of every medication as well as all of the potential side effects and ways in which his progress would be measured. Because his personal needs often swallowed up a lot of appointment time that I could not always afford, I enrolled DQ into a manufacturer’s nurse program. DQ’s assigned nurse was able to spend the needed time on the phone with him explaining how his drug regimen worked, the potential risks and benefits, and expected outcomes.

Of course, each patient is an individual, and some may straddle multiple colors/quadrants, but being proactive in thinking about what to expect before you open the exam room door may help maximize the quality of your time with each patient.

AUTHOR PROFILE: Iris Zink, MSN, NP, RN-BC is a nurse practitioner at Lansing Rheumatology in Lansing, Michigan, and Immediate Past President of the Rheumatology Nurses Society.

AUTHOR PROFILE: Iris Zink, MSN, NP, RN-BC is a nurse practitioner at Lansing Rheumatology in Lansing, Michigan, and Immediate Past President of the Rheumatology Nurses Society.

References

1. University of Michigan Ross School of Business. Competing Values Framework. Available at www.michiganexecutiveeducationasia.com/wp-content/uploads/Michigan-Ross-Competing-Value-Framework.jpg. Accessed May 9, 2017.

2. Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3-15.