As a dermatology nurse practitioner, psoriasis is one of the most common conditions that I encounter on a day-to- day basis. Psoriasis affects more than 8 million adults worldwide. Studies have shown that approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis will eventually develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Along with a myriad of comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and depression, the impact of PsA on a patient’s overall quality of life can be significant, especially among those with severe disease.1 Given the multisystem impact of psoriatic disease, a collaborative, interdisciplinary approach to care that involves both dermatology and rheumatology teams is critical to provide our patients with the most holistic, comprehensive, and streamlined levels of care. 2,3

While this partnership may seem to have obvious benefits, in the majority of health systems throughout the United States, we continue to practice in silos. This compartmentalized level of care leads to delays both in diagnosis as well as treatment. This issue of Rheumatology Nurse Practice offers a look at a variety of potential collaborative settings, ranging from a formal, combined rheumatology-dermatology clinic to a very informal, 1-on-1 relationship between providers. There are, of course, varying levels of logistical barriers and bureaucratic headaches depending upon the setup of the collaboration.

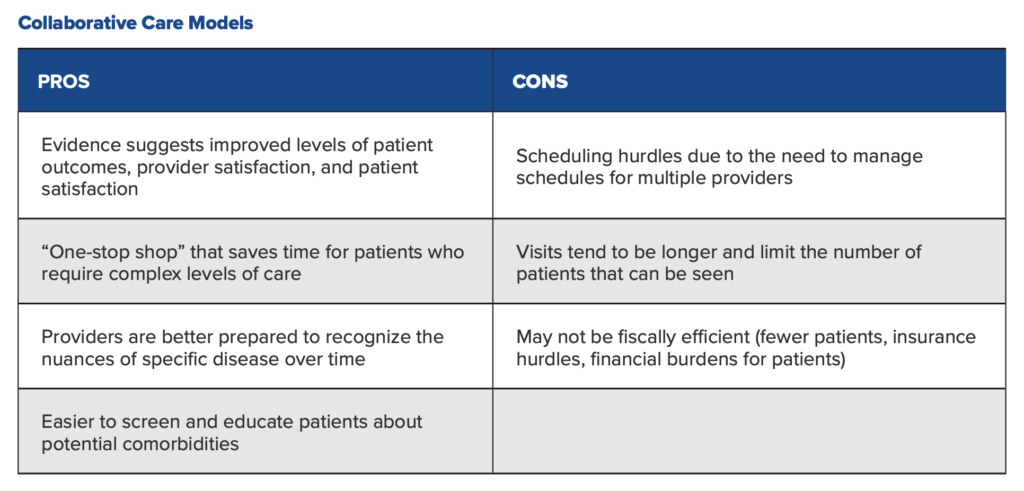

Let’s start by looking at some of the primary pros and cons of a formal collaborative rheumatology-dermatology setup. 2-4

At my academic practice, we do not have a formal combined rheumatology-dermatology clinic, though our team certainly understands the importance of collaborating across walls for our patients with psoriatic disease. While we see our patients asynchronously, we have established a strong referral system with rheumatology that allows us to send over patients who require urgent evaluation for possible PsA. Our patients certainly appreciate that they don’t have to wait months for a rheumatology referral once a member of our dermatology team suggests to them that they need one.

Of course, this model is not without its challenges. The most significant challenge I have faced with this model is access. Access is a two-way street. There always seem to be more patients that need to be seen than there are open scheduling slots for them. This may lead to frustration on the part of both the patient and provider, which then leads to delays and potentially disjointed care. This is especially true in an academic medical center like ours where most of the physician faculty have only one or two windows per week in which they see patients (the remaining time is spent attending to research and other non-clinical responsibilities). While our team of advanced practice providers can help to fill that gap, it does require the right education and training to be able to care for such a highly specialized group of patients. Personally, it took me several years practicing in dermatology before I felt comfortable in managing psoriatic patients independently. Our rheumatology department has recently added a nurse practitioner to help improve access for our PsA patients, which has been an incredibly helpful step in the right direction. Nonetheless, the number of dermatology providers in our department significantly outnumbers the number of rheumatology clinicians in our center specializing in the management of PsA, further accentuating the mismatch between supply and demand.

For starters, we never let a psoriasis patient leave the exam room without asking them about joint issues. The vast majority of patients who develop PsA initially present with skin findings, and many simply don’t associate joint pain and swelling with their psoriasis, so it’s important that we reiterate this link to them at every visit. A positive report of new or worsening joint symptoms triggers an automatic referral to rheumatology.Our dermatology clinic is well versed in the link between psoriasis and joint disease, and we have developed a variety of best practices to make sure that we don’t overlook patients whose disease may be accelerating.

Second, we are strong proponents of educating our psoriasis patients about potential comorbidities of their disease. This will sometimes trigger a patient to tell us, “You know, I have been noticing that XYZ has happening recently.” If nothing else, it makes them more aware of self-monitoring for specific issues that are more common among psoriasis patients.

Third, we emphasize the importance of establishing care with a primary care provider (PCP) for those patients who do not have one they see on a regular basis. The PCP should be the one screening for common comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease at recommended intervals.

Last, but certainly not least, we screen all of our psoriasis patients for depression. Many studies have demonstrated the link between depression, anxiety, and suicidality among patients with psoriasis. Let’s look at how the process works for a specific patient in our practice.

“The systemic, multisystem nature of psoriatic disease…warrants each of us to look at our respective practices to see where the gaps in care delivery exist and identify opportunities for professional collaboration.”

In October 2020, I met Alexia for the first time. A 43-year-old female with single nail dystrophy, Alexia came to us after being referred by her PCP. She had been prescribed a topical antifungal 6 months before she came to us that failed to resolve her issues. Following a physical exam, my immediate suspicion was psoriatic nail disease based on Alexia’s history and clinical presentation. Nail dystrophy is extremely common in patients with PsA, with an overall prevalence of between 80-90%,1 so I also asked Alexia about joint-related symptoms. It turns out that she had been struggling with persistent low back pain for approximately 3 years following the birth of her last child, along with morning stiffness that lasted for several hours every day. She told me it had gotten so bad that she needed to modify her seated position while breastfeeding simply to be able to withstand the pain. Certainly, this report raised my suspicion of a diagnosis of PsA even more.

With the exception of nail dystrophy on her right ring finger, there was nothing else abnormal about Alexia’s physical exam—not a silvery scale anywhere on her body. I sent a nail clipping to our dermatopathology department for evaluation and simultaneously reached out to a rheumatology colleague within our network for an urgent evaluation. He was able to see Alexia a few days later and quickly diagnosed her with axial PsA. Three months later, Alexia’s back pain had completely resolved thanks to the introduction of adalimumab, and she told me she was feeling better than she had in years. This is obviously an optimal outcome, and there are many patients whose short-term progress is not as substantial as Alexia’s, but this nonetheless points to the importance of working together for all of our patients who may benefit from a collaborative approach.

There are undoubtedly challenges to finding the best collaborative model based on your own practice setting. There are many standalone dermatology clinics in the United States who are not fortunate enough to have a formal relationship with a rheumatology practice. These providers may need to seek out colleagues who are interested in working with members of their team. The systemic, multisystem nature of psoriatic disease and its comorbidities warrants each of us to look at our respective practices to see where the gaps in care delivery exist and identify opportunities for professional collaboration. Closing these gaps will help minimize delays in diagnosis and optimize outcomes for our patients.

References

1. Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):545-68.

2. Soleymani T, Reddy SM, Cohen JM, Neimann AL. Early recognition and treatment heralds optimal outcomes: the benefits of combined rheumatology- dermatology clinics and integrative care of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis patients. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;20(1):1.

3. Theodorakopoulou E, Dalamaga M, Katsimbri P, Boumpas DT, Papadavid E. How does the joint dermatology-rheumatology clinic benefit both patients and dermatologists? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13283.

4. Okhovat JP, Ogdie A, Reddy SM, Rosen CF, Scher JU, Merola JF. Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Clinics Multicenter Advancement Network Consortium (PPACMAN) Survey: Benefits and challenges of combined rheumatology-dermatology clinics. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(5):693-694.

AUTHOR PROFILE: Veronica Richardson, MSN, ANP-BC, DCNP is a dermatology certified nurse practitioner who currently practices in the Department of Medical Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia, PA.

Participants will receive 2.75 hours of continuing nursing contact hours by completing the education in our course:

The Intersection of Dermatology and Rheumatology in the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis