The treat-to-target approach to care is a hot topic in medicine and is now widely accepted as a best practice in our patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We read about it in the literature and hear about it at conferences regularly. The evidence in other rheumatic disease states such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA) isn’t quite as clear cut.

PsA has at least five distinct domains—joints, spine, skin and nail disease, dactylitis, and enthesitis. This makes quantifying disease activity very challenging. In our clinic, we utilize two well-known disease activity measures commonly used in patients with RA—the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)—to assess our PsA patients as well.

The DAS28 measures disease activity in the shoulders, elbows, wrists, metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, and the knees. It also includes either a C-reactive protein (CRP) level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), along with a patient global assessment of disease activity. In the absence of either a CRP or ESR, our practice uses the CDAI. The CDAI is essentially identical to the DAS28 with the exception of a lab value. While the DAS28 and CDAI are both excellent assessors of disease activity in RA, their clinical utility in PsA is not as strong since both tools exclude many of the disease domains found in patients with PsA.

So then why use them in our practice? Primarily, it’s because the DAS28 and CDAI calculators are built into our electronic medical record. All we need to do is enter in the respective values, and the calculation is performed automatically. As noted in this issue of Rheumatology Nurse Practice, there is not yet a disease activity measure that is considered a gold standard in patients with PsA, so it’s hard to feel like we are missing out on something wonderful. Even though we use tools built for RA, measuring something is still better than measuring nothing, and sometimes tracking of results can truly be clinically meaningful.

Let me share with you an example.

JD is a 53-year-old female patient I have followed for a number of years. She was diagnosed with psoriasis in 2001, followed by a diagnosis of PsA a decade later. Prior to being treated with biologic therapy, JD’s psoriasis was mostly limited to her scalp and elbows; once she began a biologic, she has had only a few outbreaks of psoriasis mainly limited to her elbows during flares.

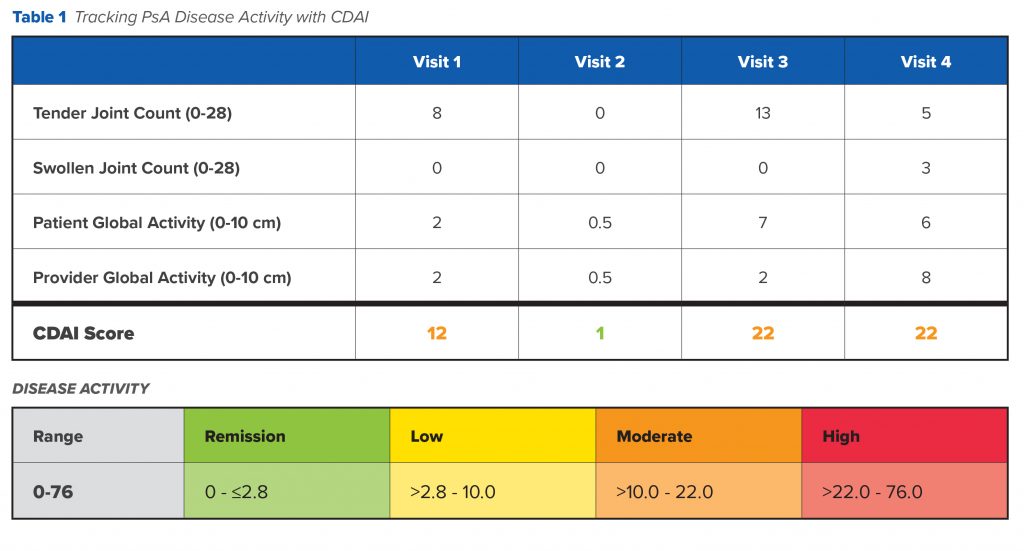

Besides joint and skin disease, JD has also had a few flares of enthesitis. She has never had dactylitis. Her treatment course has mainly been driven by joint symptoms as this is her primary quality-of-life issue. Figure 1 illustrates how her disease has tracked with the CDAI in the last several years.

The first time I met JD, her treatment regimen included etanercept and methotrexate (MTX). She initially presented as an urgent consult due to increased pain and swelling of the finger joints and bilateral knees. She had not taken etanercept for approximately 6 weeks due to a recent skin infection and only restarted it a few days before our initial meeting. JD’s CDAI score was 12, indicating moderate disease activity (Visit 1). Since she had just resumed taking etanercept—which had worked well for her in the past—JD was willing to wait a few more weeks to see how her joints would respond before making significant adjustments to her treatment regimen, although I did add meloxicam 10 mg QD on a temporary basis.

JD came back to see me 3 months later. She was feeling much better, stating it was the best she had felt in years. She denied having any joint pain, swelling, or stiffness. There was no visible psoriasis, no enthesitis, and no dactylitis. Her CDAI score was 1, indicating disease remission (Visit 2). We were both very happy with her progress, especially as the CDAI score matched JD’s self-reported improvement.

About a year later, JD came back into my office. Things had gotten significantly worse. JD complained of persistent joint pain, swelling, and increased stiffness throughout the day. She also had psoriasis on her elbows. I performed another CDAI, and her score rose back up into the moderate disease activity range (Visit 3).

Based on this information, we were at a tricky crossroads. JD remained on etanercept and MTX, which had previously been so effective, but was clearly no longer working at well as it once did. Given JD’s symptoms and level of disease activity, we began with a discussion of possibly increasing her dose of MTX from 10 mg QW to 15 mg QW. However, after her liver function test results came back elevated, we shelved that plan. We instead decided to boost the dose of meloxicam to 15 mg QD in the short term. A month later, we repeated the liver function test with the same result as previously, so MTX was discontinued and we switched to leflunomide 20 mg daily.

Unfortunately, shortly after this modification, JD had an emergency cholecystectomy that resulted in minor complications. During the procedure, she was found to have ulcerative colitis, which required further modifications in our treatment of her PsA. We switched JD from etanercept to adalimumab since that drug also has an indication for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. JD also decided to discontinue leflunomide due to persistent gastrointestinal side effects.

JD’s most recent CDAI completed 3 weeks ago still shows moderate disease activity (Visit 4), but she is reticent about making further medication changes due to the recent upheaval in her overall health. She is recovering from her surgery and bowel disease, and just recently decided to retire and buy a house in Florida. She feels the move will have a positive impact on her quality of life and disease activity. We shall see what subsequent visits show.

While the DAS28 and CDAI are not the optimal tool to assess and track the full range of PsA disease activity in a patient like JD, their use at least has given us a quantitative figure that we can point to and substantiate improvement or worsening of disease. This helps us broker a more open discussion of disease activity and set clear goals of therapy. Hopefully in the future, we’ll have better disease measurement tools in PsA that can be easily incorporated into the patient visit and provide a clearer picture of the spectrum of PsA activity, but for now, we’ll do the best we can with what we have.

AUTHOR PROFILE: Linda Grinnell-Merrick, MS, NP-BC, is a board-certified nurse practitioner at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York, and the President of the Rheumatology Nurses Society.