Lupus is a chronic disease that requires long-term care, which can pose a significant challenge to the patient and health care team.

There are many epidemiologic, socioeconomic, and psychosocial factors that come into play that make this a complicated disease to manage.

Patients with lupus are often young women, with some ethnic groups such as African-Americans and Hispanics being prone to more severe disease.1 Quality of life is often severely reduced by unpredictable and fluctuating disease flares, along with side effects related to lifelong treatment. Socioeconomically, we have many patients with lupus who are unable to maintain regular employment and pay for health insurance. Frequently, these patients will only seek health care when they visit a hospital emergency room in a crisis.

Recognizing these persistent issues, my hospital recently created an initiative that identifies lupus patients at high risk of nonadherence and enrolls them in a quality improvement program. This program matches the patient with a comprehensive team that includes a rheumatologist, a registered nurse, and a social worker, among other professionals. The goal of this program is to decrease hospital admission rates, improve overall adherence, increase family involvement, get patients more involved in social activities, improve patient and family knowledge on lupus, and provide educational sessions on lupus to community providers. This program was made possible through a foundation grant that focuses on at-risk populations and will run for 2 years.

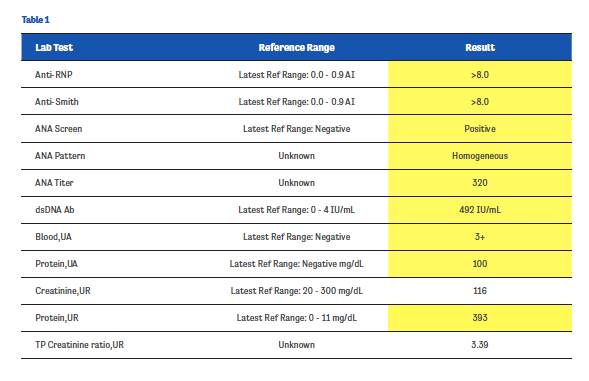

One of the first patients enrolled in this program was MG, a 20-year-old African-American female. MG presented to our office with general fatigue, multiple arthralgias, and facial rash. Her initial lab results, which are shown in Table 1 (values in yellow fields indicate abnormal results), were highly concerning, leading us to expediate her care and admit her to the hospital. There, MG received a renal biopsy and was started on high-dose corticosteroids.

Initially, MG was adherent to her follow-up care, coming to our office as scheduled for the first few months. Tapering her off corticosteroids, however, proved to be challenging—MG rarely remembered to bring her medications to her clinic visits and she could seldom recall the dose she was taking.

Things really began spiraling downhill about 6 months after we began seeing MG when her mother, who suffered from alcohol and drug addiction issues, kicked MG out of her house, forcing her into homelessness. Suddenly, MG had no money, no home, and no phone. Not surprisingly, she stopped taking her medications soon after.

For the next 2 years, MG lived a topsy-turvy life, bouncing between her sisters’ houses and homeless shelters. There were many missed appointments at our clinic; we often only received updates on MG’s condition when she ended up in crisis in the emergency room. MG was extremely difficult to contact due to her lack of engagement and rare ownership of a cell phone. She frequently ended up in the emergency room, yet often left against medical advice once she felt she was better. She would tell us her medications “tasted bad” or that she “couldn’t find them” when we asked why she was nonadherent to her treatment plan.

MG was one of the first patients we enrolled in our QI initiative. At the time we rolled out our plan, her life was beginning, at least to a small degree, to stabilize. She had recently turned 22 years old and was living in a private room at the YMCA (though she sometimes spent several days or weeks at her sisters’ houses). She had obtained a free “Obama phone,” although it was rarely functional. She had also enrolled in Medicaid and was receiving both Social Security disability as well as food stamps, although her status was tenuous due to missed classes and follow-up appointments with social workers.

We met with MG during one of her emergency department visits and explained to her what the QI program entailed. We knew that MG had made a previous connection with an RN in her primary care provider’s office, so we recruited that nurse to be part of our initial connection team. We never pressured MG to participate in the QI program, but delicately explained during several subsequent emergency department visits how this new program would be beneficial to her well-being.

Working hand-in-hand with a social worker who was part of the QI team, we engaged MG to determine her specific needs. We began to set up calls and texts both to MG and her sisters for appointment reminders as well as reminders for pre-appointment lab draws. We placed a call to a local food pantry and set up appointments for MG to go grocery shopping. Our nursing team provided education regarding MG’s medications and the dangers of medication nonadherence. Our team also coordinated with our hospital pharmacy so that MG could fill her prescriptions on site and leave with her medications in hand. We maintained close contact with MG’s primary care office through our electronic medical record and phone calls. In sum, our program was designed so that MG would no longer fall through the cracks.

It’s only been approximately 4 months since we put the latest plans in place. Since then, MG has shown up for 2 follow-up appointments—1 with her rheumatologist and 1 with her primary care physician—and has gotten her labs test drawn as scheduled. Her medication adherence is still a bit spotty, but it’s much improved from where we began. Slowly, it seems as if MG is gaining trust in our team and is becoming more engaged in her care.

Building communication between the primary care and rheumatology offices has been vital to our success. It’s not always an easy bridge to build, but we have found that exchanging messages in the electronic medical record and quick phone calls when necessary can make all the difference in a patient like MG. Seeing improvements not only in our patients’ health but their faith and trust in their healthcare team is one of the most rewarding parts of our job. We’re hopeful to have more patients like MG in the future who buy into our new team-based system.

AUTHOR PROFILE:

AUTHOR PROFILE:

Linda Grinnell-Merrick, MS, NP-BC, is a board-certified nurse practitioner at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, NY, and the President of the Rheumatology Nurses Society.

Reference

1. Somers EC, Marder W, Cagnoli P, et al. Population-based incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: The Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance Program. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:369-378