It’s 6:30 a.m. and that pesky alarm clock is going off … for the third time. I lay in bed for another 10 minutes, mentally logging which number I’m at on the standard 0-10 pain scale (0=no pain to 10=excruciating pain). Today feels like it’s going to be a 4, which is pretty good for me after living with chronic pain—specifically rheumatoid arthritis (RA), fibromyalgia, and chronic migraine—for more than half of my 42 years.

Each morning after I wake up, I run through my seemingly never-ending mental to-do list. Do I need to go shopping? How many meetings do I have on my calendar? Can I work from home, or do I need to go into the office? And so on. I then think about what will be required to cross each item off my list. Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a lifesaver for me and means I’ll be more productive for one very important reason—I’ll use up less spoons that I otherwise might have.

Before you scratch your head too much figuring out what I’m talking about, let me give a little background on the Spoon Theory. I was introduced to the concept in 2013, when its creator, Christine Miserandino, launched #SpoonieChat on her blog. The Spoon Theory is based on the idea that someone dealing with chronic illness has a limited amount of energy at the beginning of each day.1 On her blog, Miserandino, who suffers from lupus, describes how she explained the Spoon Theory to her friend.

“The idea of quantifying energy as ‘spoons’ has allowed me to convey to my friends and family what my day-to-day life is like.”

While sitting in a diner, she handed her friend 12 spoons, explaining that each spoon represents a unit of energy. She then asked her friend to list the typical activities she performs in a single day.

As her friend ran through her list of tasks for the day—showering, getting dressed, standing on a train, walking to the office, etc.—Miserandino took away one spoon for every task. By the time her friend got through half her day, she only had three spoons left. “Once the spoons are gone,” Miserandino told her, “so is your energy for the day. You can’t do anything more until tomorrow.”

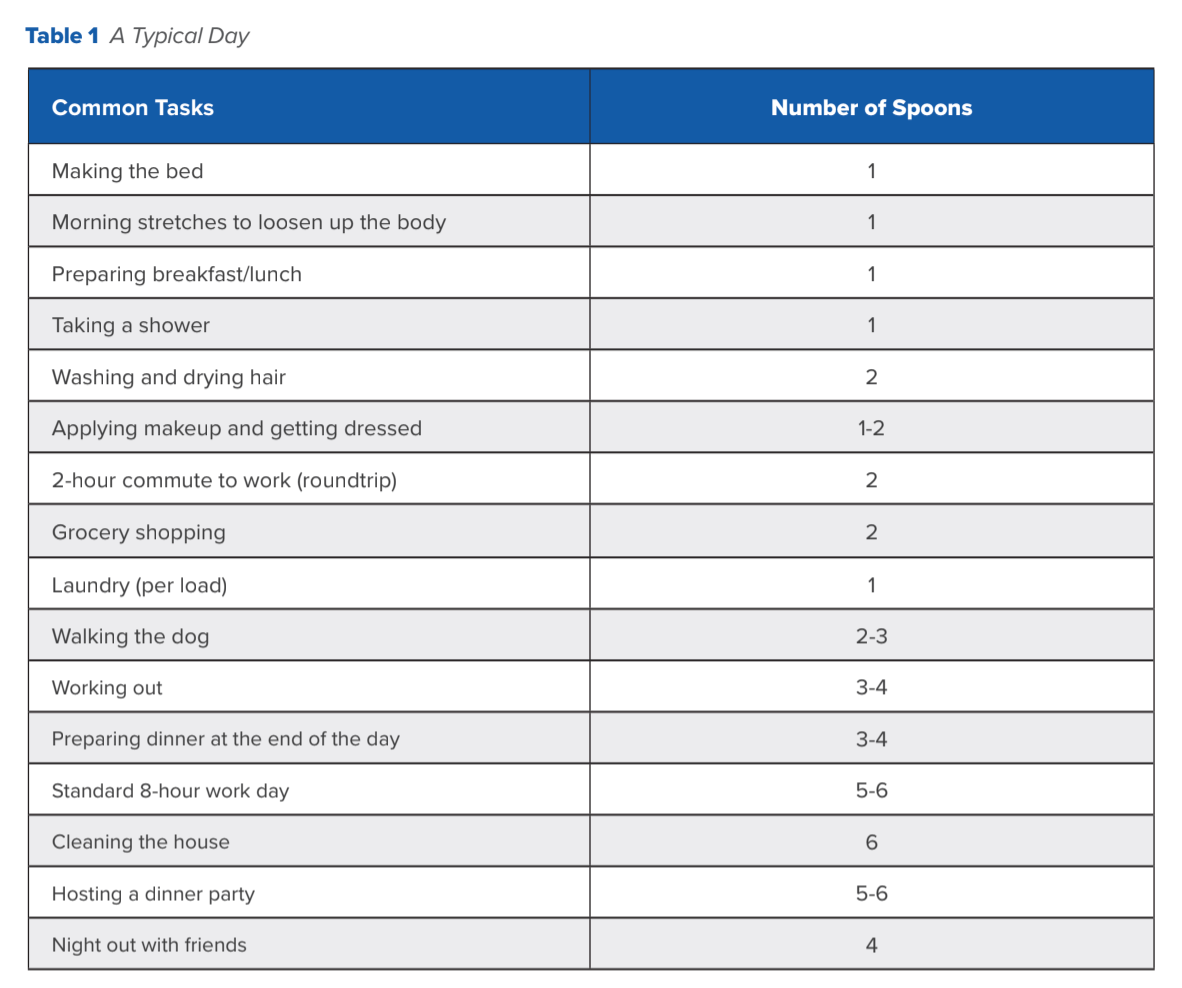

Every task we perform, whether you have a chronic disease or not, takes up a certain amount of energy. The idea is that effortless tasks for most people—getting out of bed, taking a shower, getting dressed, making breakfast—are a little bit more complicated and take a lot more forethought for someone with a chronic disease. Depending on how we are feeling, it can be a struggle to simply get out of bed. Preserving your “spoons” is about rationing your energy, being mindful of each task, and understanding and weighing the consequences of going beyond your energy limit. It’s about balancing the day to day and understanding your limitations (see Table 1).

I’ve embraced the Spoon Theory as an easy and effective way to explain to others what living with chronic pain feels like. I have lost count of how many times I have heard, “But you look fine!” While I appreciate the sentiment, after 25+ years of struggling with RA and its myriad secondary conditions, I’ve mastered the healthy facade and fake smiles. The idea of quantifying energy as “spoons” has allowed me to convey to my friends and family what my day-to-day life is like. They now understand what it means when I say, “I’m out of spoons.”

Let me give you an example of how this works. As I mentioned earlier, I woke up in the morning feeling like today was going to be a “4” on the pain scale, which is not too bad. Consequently, I assigned myself 14 spoons for the day. I then thought about everything I needed to get done— the laundry, the work assignments, the day-to-day minutiae that most of you probably don’t even think about—and calculated in my head how many spoons I would need to assign to each task. Most are one-spoon tasks, but a few can take two or three spoons. One of my biggest considerations each day comes at dinnertime. I am often exhausted by the time my workday is over, and cooking dinner is a task I usually dread. It can be a three or four spoon task. I know if I push to keep going after I’ve run out of spoons, I’ll end up paying for it tomorrow…and the next day… and the next. So takeout it is tonight!

I am extremely fortunate to have a supportive family who understand my situation. My partner often offers to lend me his spoons—while he says it somewhat in jest, what it tells me is that I can lean on him for support when I need it most. I know I won’t face any judgement if I need to crawl into bed at 5 p.m. because it’s already been a long day and I’m simply DONE.

While it’s important for individuals suffering with a chronic illness to be able to effectively communicate with their friends and loved ones, it’s equally important for them to have an open and honest relationship with their team of healthcare providers. I have lost count of the number of rheumatologists I’ve seen over the years. If I don’t feel comfortable in the first visit, or if I feel that they are not truly listening to me, I move on. As a patient with a longstanding chronic disease, no one knows my body and symptoms better than I do. When I talk to my provider, I need them to understand the limitations that my disease places upon me.

So the next time your patient smiles and says they’re doing “Fine,” think about what it takes for them to navigate life on a limited energy supply. Learn to look past the “Fine” to determine if they are truly the “3” that they say they are, or if their energy supplies are already depleted for the day and they just want to go home and crash. Using the Spoon Theory is a great way to foster open communication with your patients and really dig down into their day-to-day life. Are you their first spoon of the day or their last?

References:

1. Miserandino C. The Spoon Theory. Available at butyoudontlooksick.com/articles/written-by-christine/the-spoon-theory/. Accessed September 15, 2021.

Author Profile: Callie Krakauskas is a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who lives and writes in Springfield, VA

Participants will receive 2.75 hours of continuing nursing contact hours by completing the education in our course: Rheumatology Nurse Practice: Healthcare Disparities in the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis

Take the Course!