The challenges of medication adherence in children are as diverse as the populations we serve. Among other things, adherence in children can be affected by parental beliefs, medication taste, smells or side effects, pain associated with route of administration, peer reactions, the child’s own stage of development, and responsibility given to the patient by parents to manage medication administration. The list of potential factors is long.

In a recent issue of Rheumatology Nurse Practice, we discussed the importance of parental support by providers and nurses to help parents effectively guide their child with a chronic disease. The last thing any parent wants to hear is that their child has a chronic disease and will likely need more than one medication to keep their organ and body systems from becoming damaged by the effects of the disease. Healthcare providers must be sensitive to this fact as they guide parents through their initial grieving process. The parent may grieve for the healthy child they had and/or the pain their child is currently experiencing, as well as suffer anticipatory grief as they foresee how their child’s future will be impacted by their new diagnosis. Much of the guidance with the anxious, grieving parent should be done “behind the scenes” and not in front of the patient. The provider and parent need to be very open and honest with each other. I’ll talk more about this later in this article.

Now that we’ve briefly addressed the parent component, let’s turn our focus to the child. As healthcare providers, our developmental assessment of the child begins at the moment of initial eye contact and introduction. As we gain experience with the specific child, we fall into the relationship almost through muscle memory—we talk to them and interact in a manner that we don’t have to think about.

As we try to build trust with the child, it’s important to get buy-in on both simple tasks such as the taking of vital signs as well as more intrusive components such as the physical examination. Through this process, we can determine if the child is generally easy going, difficult, or a little of both. We’ll also be able to gauge how supportive the parent will be (do they force the child to cooperate? Are they disengaged?). Comments from the parent may also help us understand the child’s temperament and personality.1

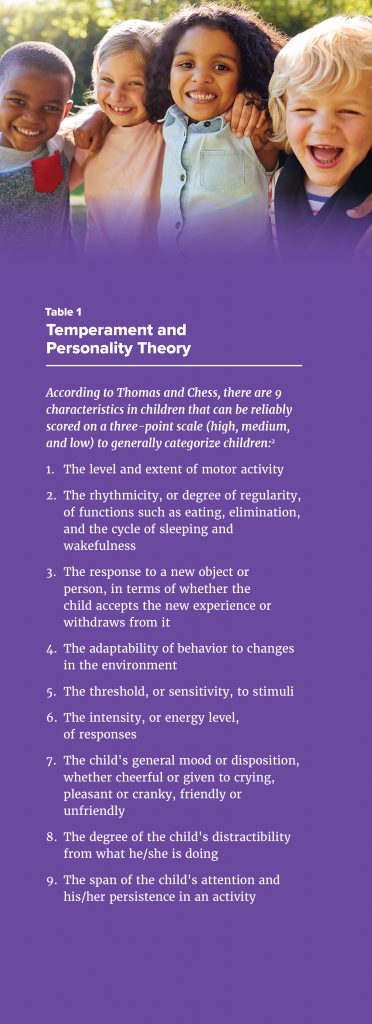

Thomas and Chess’s Temperament and Personality Theory states that there are nine temperament characteristics that affect how well a child fits in at school, with their friends, and at home (Table 1).2 These characteristics are used to categorize a child as easy going, difficult, or slow to warm up. While many children fit neatly into one of these broad categories, as many as 35% will have significant overlap.3

As providers, it is important from the start that we model calm, firm, and loving behavior toward the child and parent. We need to show the parent how to modulate their response/behavior in their child’s presence since children pick up on parental emotions very quickly and will often respond based on what they are sensing. Children are exceptional at picking up on parental fear and mimic this fear in their own developmental ways. It may be displayed as crying or being uncooperative during the exam. When a parent fears that a medication may be dangerous for their child, the child’s fear may be displayed as pretending to swallow/take medication while instead hiding pills under the carpet or putting them in the trash.

Now that we’ve addressed some of the most important factors influencing a child’s medication adherence, let’s shift to talk about environmental influences.

Several researchers have noted the important role that a child’s environment plays with regard to temperament and personality, as well as attainment of developmental milestones.1-3 This is why it’s so important that we make sure our patient’s weight is following age-based growth trends and if not, why that may be. Is food inadequacy a problem? If so, are there community resources you are aware of that you can point families toward?

Perhaps this is a child whose family has moved several times in the past year. Is there stable shelter available to them, or were they recently evicted and had their belongings thrown into the garbage, including the child’s precious comfort blanket (this happened to a recent patient of mine and it was heartbreaking)?

Worst of all, did a parent lose their job because they needed to be “on call” around the clock to care for their child with a chronic illness? That can cause unimaginable stress.

It can be too easy as healthcare providers to be judgmental when we learn that a child hasn’t, for instance, taken their methotrexate for the last 3 weeks, but there are sometimes significant environmental influences impacting the lives of the child and family. It’s important therefore to ask parents if there have been any significant changes in their lives since we last saw the child and offer whatever assistance we can—even if it’s just a compassionate ear—to help with short- and long-term adherence issues. These are extremely vulnerable children and families who we care for.

In my experience, the children who seem to have the best adherence rates are those who Thomas and Chess would describe as “easy going,” come from emotionally and physically stable environments, have parents who nurture and protect them in a healthy manner, and have an open dialogue with their healthcare team.

Nurses have been providing family-centered care for decades, with numerous studies showing that engagement of the patient and his/her supportive care team leads to the best patient outcomes.4 Table 2 offers some concrete suggestions on ways to assist children and their families in overcoming adherence barriers at various stages of their life. With children and their families, having the emotional intelligence to understand the child’s temperament and environmental challenges will help in the development of open, honest relationships.

References

1. Huff C. Raising a Child with Arthritis: A Parent’s Guide. Arthritis Foundation; Atlanta, GA: 2010, pgs. 65-73.

2. Thomas A, Chess S, Birch HG. The origin of personality. Sci Am. 1970;223(2):102-9.

3. Burns CE, Dunn AM, Brady MA, Barber Starr N, Blosser CG. Pediatric Primary Care 5th Ed. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2014.

4. Clay AM, Parsh B. Patient- and family-centered care:

AUTHOR PROFILE: Cathy Patty-Resk, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-PC is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner in the Division of Rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Michigan in Detroit, MI, where she provides medical services to inpatient and outpatient pediatric rheumatology patients. Cathy is also the President-Elect of the Rheumatology Nurses Society.