A chapter from HANDLING THE HARD QUESTIONS:

What Our Patients Are Asking Us About Rheumatic DiseaseRead and download this booklet on our Workforce Resource homepage

Each day, rheumatology nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants field dozens of questions from their patients with rheumatic diseases, and they need to be able to properly and effectively communicate appropriate responses. This pocket guide includes a brief summary of evidence surrounding some of the most common—and challenging—questions that patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, and systemic lupus erythematosus are asking about. We hope you find this guide useful for your professional development and that it assists you with your day-to-day patient management.

How did I get Lupus?

Lupus is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory autoimmune disease, with many different clinical signs and symptoms due to its effects on multiple organ systems and tissues. When people talk about lupus, they are often referring to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the most common form of lupus.1

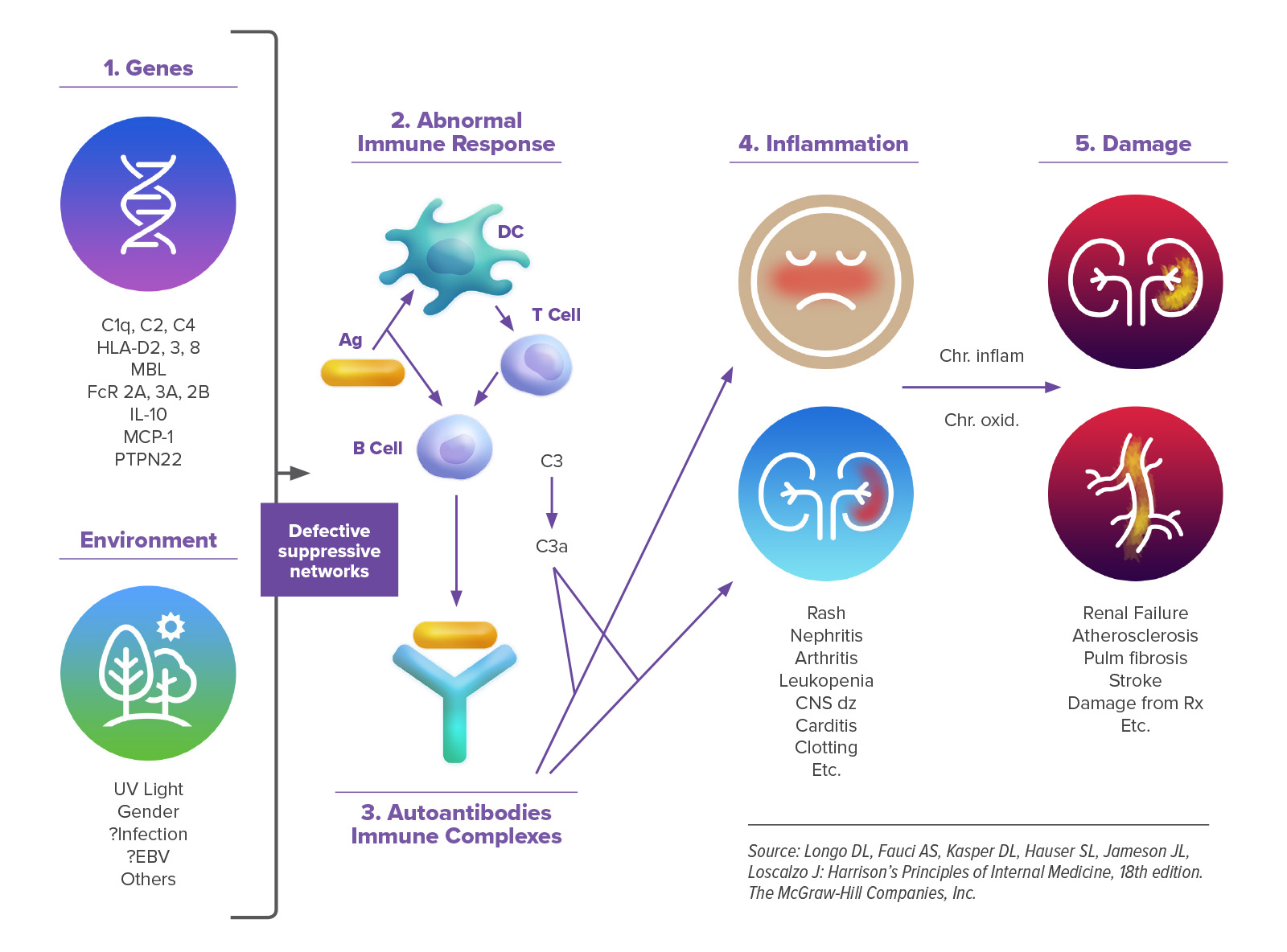

The cause of SLE is multifactorial, but is thought to be due to a combination of genetic, hormonal, immunologic, and environmental factors (e.g., ultraviolet light, certain viruses).1 One of the biggest risk factors for developing SLE is gender. The majority of individuals diagnosed with SLE are female, with women affected 9 times more frequently than men, often during their childbearing years.2 Race/ ethnicity also plays a role, with African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and Native Americans affected more frequently than Caucasians.1

Like all autoimmune diseases, the pathogenesis of SLE is complex and involves many different players in the immune system. In all individuals, cells in the body eventually die; normally, these dead cells are cleared away simply and efficiently. However, in individuals with SLE, the mechanism to clear away dead cells is broken. As such, the dead cells aren’t cleared away as quickly as they should, and they begin to break down. As the cells degenerate, proteins that usually live inside the cells become exposed. The immune system doesn’t recognize these proteins as “self” and therefore goes into overdrive, leading to cytokine release, inflammation, the production of autoantibodies, and immune complex formation, which are deposited in various tissues throughout the body. The end result is a loss of self-tolerance and an overactive immune system, causing multi-organ inflammation and tissue damage.1,2,4

SLE is characterized by varying periods of disease flare-ups and inactivity. In addition to general signs and symptoms of a disease flare such as fever, weight loss, and fatigue, clinical manifestations of SLE can be widespread and involve numerous organ systems and tissue. The skin, musculoskeletal, and pulmonary systems are most frequently affected, although the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, renal, hematologic, and central nervous systems may all be affected as well. Renal involvement is common in individuals with SLE, with approximately 50% of patients developing nephritis, a major cause of increased morbidity and mortality.1

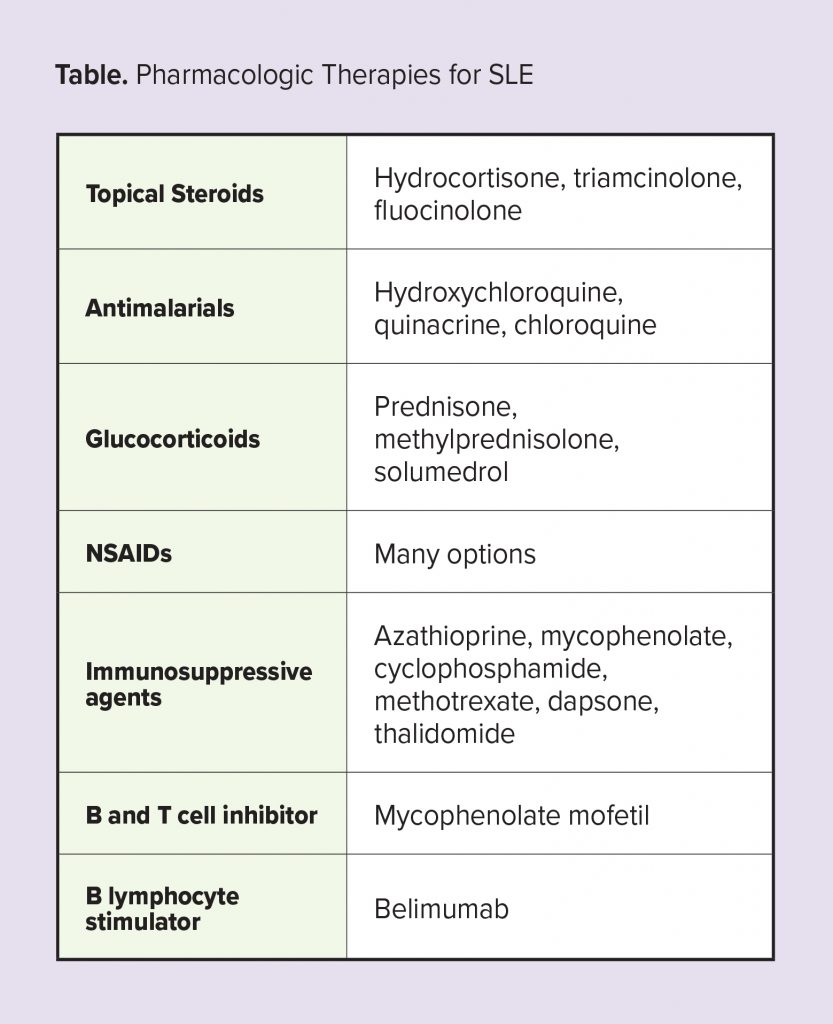

The management of SLE is complex, with the goals of therapy focused on achieving low disease activity or remission in order to reduce flares, minimize organ and tissue damage, and improve long-term survival and quality of life.5 Hydroxychloroquine forms the backbone of therapy as it reduces disease flares and symptoms. Low-dose glucocorticoids are also frequently used. The selection of other agents, such as immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents, is typically driven by the specific body systems involved.6

References

1. Maidhof W, Hilas O. Lupus: an overview of the disease and management options. P&T. 2012;37(4):240-249.

2. Bertsias G, Cervera R, Boumpas D. EULAR Textbook on Rheumatic Diseases: Chapter 20. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Pathogenesis and clinical features. Available at www.eular.org/myUploadData/files/ sample%20chapter20_mod%2017.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

3. Choi MY, Barber MR, Barber CE, Clarke AE, Fritzler MJ. Preventing the development of SLE: identifying risk factors and proposing pathways for clinical care. Lupus. 2016;25(8):838-849.

4. Lech M, Anders HJ. The pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1357-1366.

5. Tunnicliffe D, SIngh-Grewal D, Kim S, Craig J, Tong A. Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of systemic lupus erthematosus: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(10):1440-1452

6. Vu Lam N-C, Ghetu M, Bieniek M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Primary care approach to diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Aug 15;94(4):284-294.