Lesson: What Does the Future Hold in the Treatment of PsA?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a highly heritable, chronic disease found in as many as 30% of individuals with psoriasis.1 It is associated with multiple clinical phenotypes attributed to complex autoimmune or pro-inflammatory pathogenic mechanisms. PsA typically involves several clinical domains, including peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, skin and nail disease.2 Consequently, patients with PsA often experience reduced health-related quality of life (QOL) and diminished levels of productivity and functionality that are similar to patients with other serious diseases such as cancer, heart disease and diabetes.3

The combination of skin and joint involvement typically found in patients with PsA, along with chronic pain, can cause emotional distress and discomfort as well as clinical management challenges.4 Moreover, joint damage can be progressive if not adequately treated.1

The significant disease burden for patients with PsA is often underestimated. For instance, not only do patients with PsA typically rate their symptoms as more severe than their physicians, but they identify itching and the location of skin lesions as the most important factors in rating disease severity. In contrast, physicians are more apt to point to pain and joint swelling as the most important factors contributing to disease severity.5

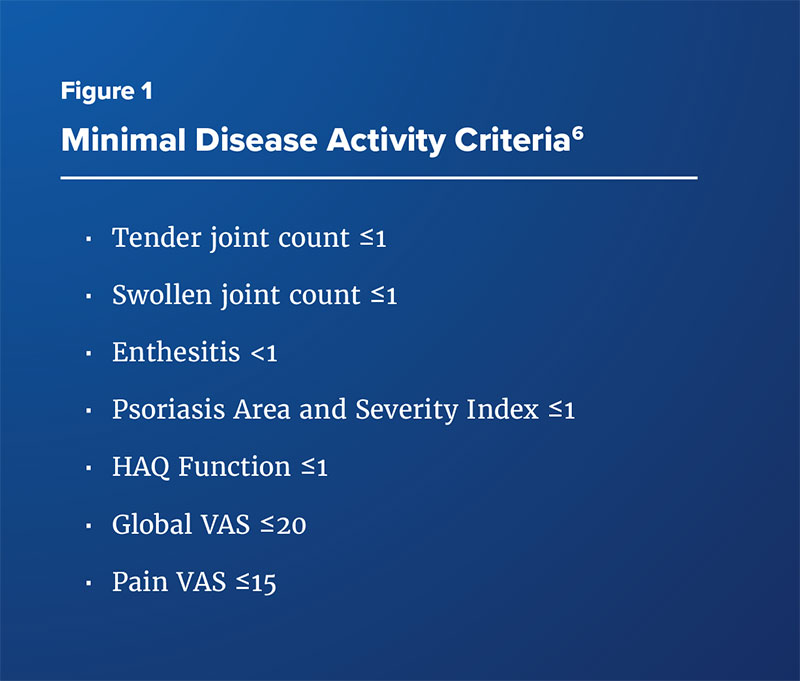

According to recommendations by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the goal of therapy in PsA is to achieve the lowest possible level of disease activity—sometimes called minimal disease activity (MDA)—by treating at least five of seven clinical domains associated with psoriatic disease, including joint and skin disease (Figure 1).6-8 However, the heterogeneous presentation and pathogenic causes of PsA may complicate treatment,2 and therapeutic approaches that address both skin and joint manifestations are imperative.

In response to these challenges, several novel agents are currently under late-stage investigation for the treatment of PsA.

Clinician and Patient Dissatisfaction with Current Treatment Options

Challenges with Using Current Therapies in Clinical Practice

The Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey is one of the largest and most comprehensive studies of clinical practice trends in both psoriasis and PsA (n=1,206). Findings from this survey showed that approximately 25% of dermatologists find managing patients with PsA to be complicated, while both dermatologists and rheumatologists find management of patients’ PsA to be time consuming.5 In addition, the survey showed that while 40% of both dermatologists and rheumatologists felt comfortable using biologic therapies for treating their psoriasis/PsA patients, rheumatologists were more likely to treat aggressively while dermatologists were more likely to not use biologic therapies at all (thus contributing to delayed PsA treatment). Costs, tolerability, and uncertainty about long-term drug safety were reasons that both dermatologists and rheumatologists cited for not initiating biologic therapy, while ineffective response posed a major barrier for specialists in continuing therapy. Authorization documentation was also considered burdensome, as was patient education and ongoing patient monitoring.5

These factors all were cited by the authors as explanation for the underuse of biologics in patients with PsA and thus, their undertreatment. A small minority of clinicians reported that many patients left their practice because they were frustrated or dissatisfied with their current treatment options due to affordability, tolerability, and/or side effects of medications.5

In particular, treatment with TNF inhibitors is frequently associated with drug discontinuation and/or loss of efficacy. In fact, recent data from the CORRONA registry showed that therapy discontinuation occurs for almost half of PsA patients within 1-2 years of initiating treatment with a TNF inhibitor.9 While GRAPPA treatment algorithms indicate that cycling between TNF inhibitors is a reasonable strategy for many patients with PsA,10 response rates from more recent clinical trials indicate that non-TNF inhibitors such as interleukins (i.e., ustekinumab and secukinumab) represent viable potential options for patients who have failed to respond to more than one TNF inhibitor.11,12

There is, however, little practical, evidence-based guidance available to guide the selecting of individual therapies following treatment failure or lack of response,13 and no validated biomarkers have been identified that would predict individual patient response to treatment.14 Moreover, there is significant variability in the extent to which individual biologic therapies control all disease domains of PsA.14 For instance, not all interleukin inhibitors effectively treat nail disease, the phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor apremilast has less efficacy for sacroiliitis and spinal disease than other agents, and T cell modulator abatacept has only been shown to improve skin and joint symptoms while ineffectively targeting other important clinical domains.2

Adherence Issues

Adherence to, or persistence with, medication is associated with treatment efficacy in PsA. However, persistence with PsA medications can be challenging for patients, and many factors, such as anxiety and depression, can contribute to low rates of adherence.15,16 Using data from the CORRONA registry, Harrold et al analyzed treatment persistence among patients with PsA who initiated therapy with anti-TNF agents with or without prior use of biologics.9 Over a 4-year period, more biologic-naïve than biologic-experienced patients persisted with treatment at 24 months (57.3% vs. 48.5%); this group also had a longer mean time to non-persistence (32 months vs. 23 months, P=0.0002).9 Shorter disease duration and less disease activity were associated with longer persistence with medication among biologic-naïve patients. A 2018 analysis of a British patient registry similarly found that at 5 years, more than half of patients with PsA had discontinued TNF treatment.17 Stronger adherence was associated with male gender, use of etanercept or adalimumab rather than infliximab, and the lack of comorbidities present at baseline.

Adverse Events

Many studies point to widespread dissatisfaction among PsA patients due to the experience of (or potential for) adverse events, the challenges associated with medication self-administration, and the constraints of concomitant monitoring required with use of biologic therapies.14 Adverse events are a significant factor in patient dissatisfaction with treatment, leading to drug discontinuation for up to 11% of patients in clinical trials.4,18,19 Side effects associated with TNF inhibitors include opportunistic, and sometimes serious, infections (e.g., tuberculosis, cytopenias), lymphoma, heart failure, hepatotoxicity and, in some cases, aggravation of skin lesions and increased risk for non-melanoma skin cancer.20,21 Apremilast, a PDE 4 inhibitor, is associated with headaches, including migraine, as well as fatigue, and upper respiratory infections. Other adverse effects associated with biologic therapies across classes include injection-site reactions (interleukins), or, in the case of infliximab, infusion-site reactions. These side effects contribute to high rates of discontinuation of biologic therapy.

The MAPP population-based survey discussed earlier in this issue also covered patient perspectives on PsA treatment (n=3,426).22 Less than half (45%) of patients were satisfied with biologic treatment and therefore discontinued therapy, most often for safety/tolerability reasons (25%) and a lack/loss of efficacy (22%). More than half (53%) were also concerned about the long-term health risks of biologic agents. Similarly, a National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) study reported adverse events as one of the main reasons that patients cite for discontinuing treatment with biologic therapies.4 In the MAPP survey, approximately half of patients also viewed biologics as burdensome due to the need for self-injection, fear of needles, or need for injection preparation.22 As a further complicating factor in treatment, patients are typically taking several drugs to control skin and joint symptoms at any one time, and experience considerable frustration with the need to cycle through and combine different therapies to achieve benefit. Unsurprisingly, as identified by the MAPP survey, both clinicians and patients emphasize the need for simplified treatment regimens and oral administration options as pressing areas of unmet therapeutic need.

Fatigue

Fatigue is an acknowledged symptom in many patients with PsA, as well as patients with other chronic inflammatory skin and joint diseases.23 Approximately 50% of patients with PsA report fatigue, and 30% report severe fatigue,24,25 both of which contribute to considerable physical and psychosocial burden, undermine quality of life, and can further exacerbate the symptoms of PsA, including pain.15,26 Although the mechanisms that cause fatigue in PsA are multidimensional, overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and resultant inflammation are considered a primary causative factor.23 Pharmacologic treatment for fatigue relies on treating the underlying disease; however, while current therapies effectively treat most or all of the current core PsA domains and reduce fatigue, none have been shown to eliminate fatigue.23 Moreover, fatigue can exacerbate the effects of disease-modifying agents such as MTX and leflunomide.

Clinical trials in PsA are increasingly including patient reported assessments of fatigue as part of the evaluation of therapeutic benefit to ensure that treatment is effective not only across physical domains but also results in quality of life improvements.27 A recent addition to the PsA core domain set that includes fatigue evaluation in clinical studies endorses this strategy and points to the need for therapies that effectively treat a wider range of PsA domains, including fatigue.28

Agents Under Late-Stage Development

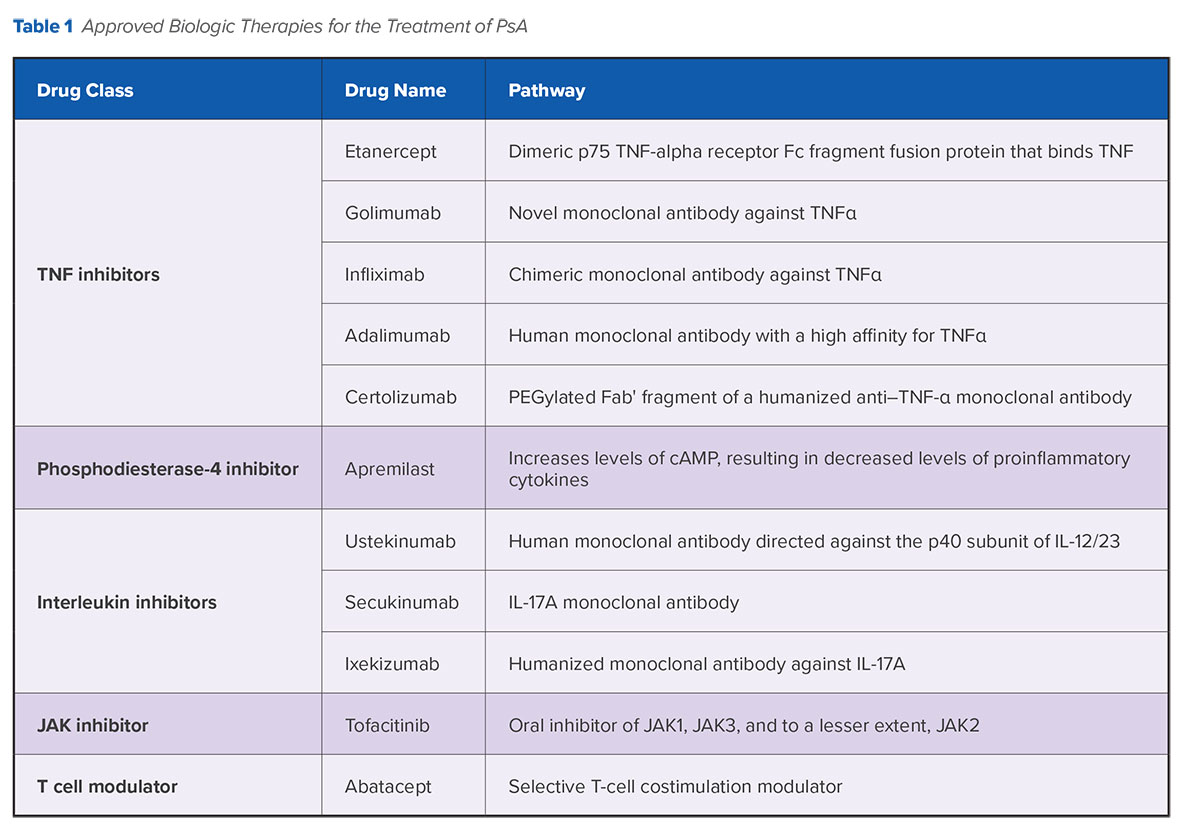

To date, five anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PsA (Table 1), along with three interleukin (IL) inhibitors (ustekinumab, secukinumab, and ixekizumab), one phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor (apremilast), one Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor (tofacitinib), and one T cell modulator (abatacept). While these biologic therapies have demonstrated efficacy in suppressing skin and joint inflammation, there are concerns about their long-term safety profiles, and the need for extensive patient education and counseling may contribute to their underuse in clinical practice.14 Many questions also remain concerning strategies for sequencing treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic therapies, including newer agents.

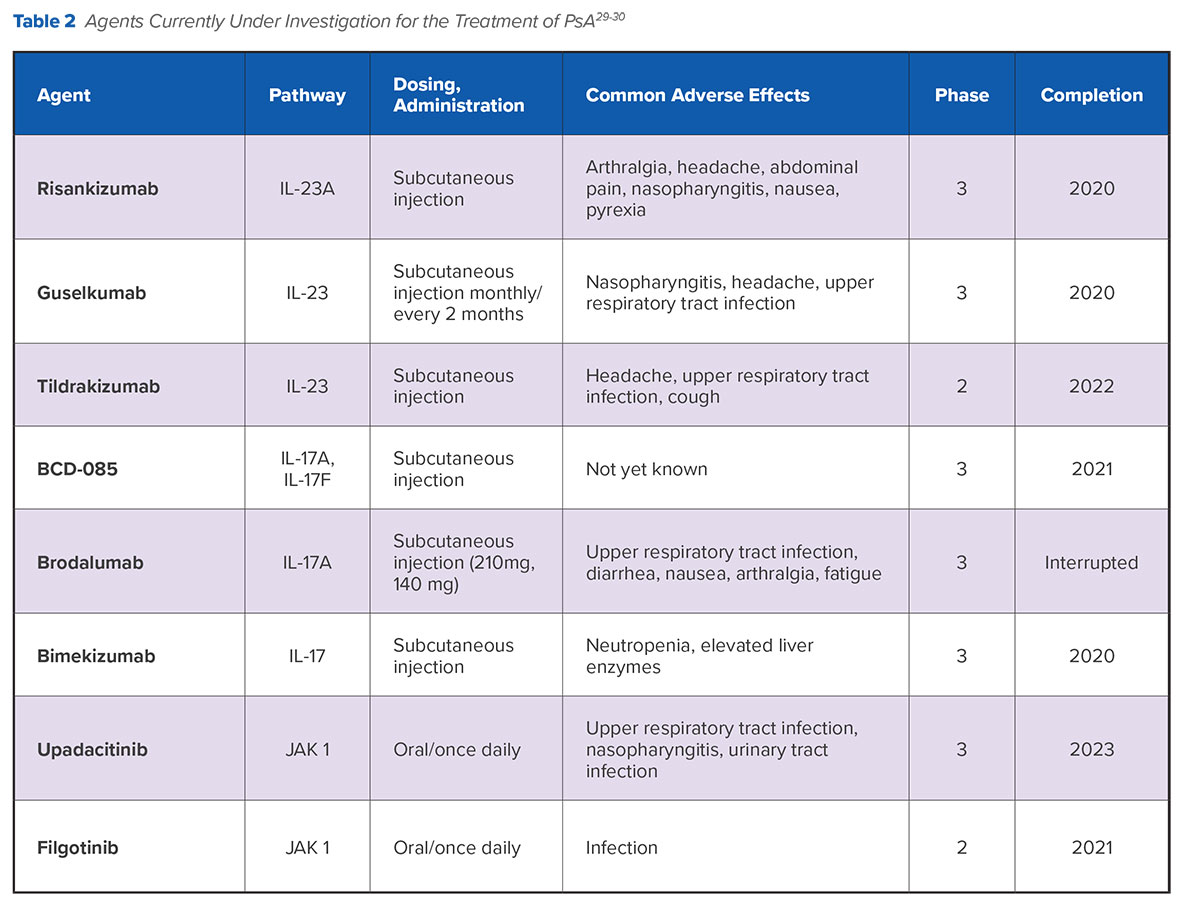

Several agents are under investigation that offer additional potential options for effective biologic treatment beyond anti-TNF therapy (Table 2). Notably, accruing evidence continues to support the observation that therapies targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathways considerably improve symptoms associated with several clinical domains of PsA.

IL-23 Inhibitors

Subcutaneously administered risankizumab selectively blocks IL-23 from binding to its p19 subunit and inhibits the role of this cytokine in psoriatic inflammation. Risankisumab has been shown to be effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and has also increased clinical responses and remission rates in patients with Crohn’s disease.31

In a phase 2 study of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, 75.3% patients receiving risankizumab achieved 90% clearance in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI90) vs. only 4.9% of patients receiving placebo and 42% receiving ustekinumab, with similar safety profiles across all three groups.32 A phase 3 trial that includes a subset of patients with PsA is ongoing.

In a phase 2 study of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, 75.3% patients receiving risankizumab achieved 90% clearance in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI90) vs. only 4.9% of patients receiving placebo and 42% receiving ustekinumab, with similar safety profiles across all three groups.32 A phase 3 trial that includes a subset of patients with PsA is ongoing.

Guselkumab, a subcutaneously administered IL-23 inhibitor, has already been established as a highly effective treatment option in psoriatic skin disease, having been approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.33 A 2018 phase 2A trial reported that use of the drug improved signs and symptoms of active PsA for 58% of patients vs. 18% in the placebo group at week 24. Guselkumab was well tolerated, with infection as the most frequently reported adverse event in both groups. A phase 3 trial is slated to be complete in 2020.34

A third IL-23 inhibitor, tildrakizumab, is a high-affinity, humanized, IgG1/., anti-IL-23p19 monoclonal antibody that has also shown benefit for patients with PsA and psoriasis in phase 2 trials.35 Following 16 weeks of treatment, PASI75 responses were 66% and 74.4% for the highest doses of 100 mg and 200 mg vs. 4.4% for patients in the placebo group (p≤0.001). Tildrakizumab was approved by the FDA in February 2018 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

IL-17 inhibitors

BCD-085 is an IL-17 inhibitor that has shown positive long-term results in patients with severe psoriasis. A phase 2 study showed a significant clinical response (PASI75) for a subcutaneous 120 mg dose in 93% of patients with severe psoriasis who did not respond to conventional therapies. Responses were sustained at one year for 98% of patients with almost complete skin clearance (sPGA score of 0 or 1).36 There were no cases of serious adverse events or early withdrawal due to adverse events. A phase 3 trial is ongoing with PsA patients.

Subcutaneous brodalumab, an IL-17 inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and has also demonstrated evidence of benefit in patients with PsA.37 However, concerns have been raised about the potential for an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in patients taking brodalumab, so its development is proceeding cautiously.38

Bimekizumab is a dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F. While IL-17A is a known driver of joint and skin inflammation in PsA, more recently it has been shown that IL-17F also contributes to chronic tissue inflammation.39 The BE ACTIVE study reported positive phase 2 results for bimekizumab at the end of 2017. At week 12, 46-79% of patients with PsA who received doses of subcutaneous bimekizumab ranging from 64 mg to 480 mg had a 90% improvement in joint symptoms (vs. 0% treated with placebo). Efficacy was dose-dependent and increased from placebo to bimekizumab 320 mg.40 Almost two thirds (61%) of bimekizumab-treated patients reported adverse events compared with 36% of placebo-treated patients; the most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection.

JAK Inhibitors

Upadacitinib is a JAK inhibitor with a high level of JAK selectivity. A phase 3 trial of patients with RA recently reported improvement in clinical signs and symptoms and similar adverse event rates across intervention and placebo groups (e.g., nauseas), although more infections were reported in the patients treated with upadacitinib.41 Upadacitinib, dosed orally like other JAK inhibitors used to treat rheumatic diseases, is currently in phase 3 trials involving PsA patients with a history of inadequate response to at least one biologic DMARD.

Filgotinib is another agent in development that is considered to have a high level of JAK1 selectivity. Phase 2 data showed an ACR20 response of 80% for filgotinib in patients with moderate to severe PsA at week 16 compared with 33% for placebo (P<0.001).42 ACR50 and ACR70 response rates were also higher for filgotinib than placebo. Treatment was well tolerated with only one serious infection in the filgotinib group and one case of herpes zoster.

Biosimilars

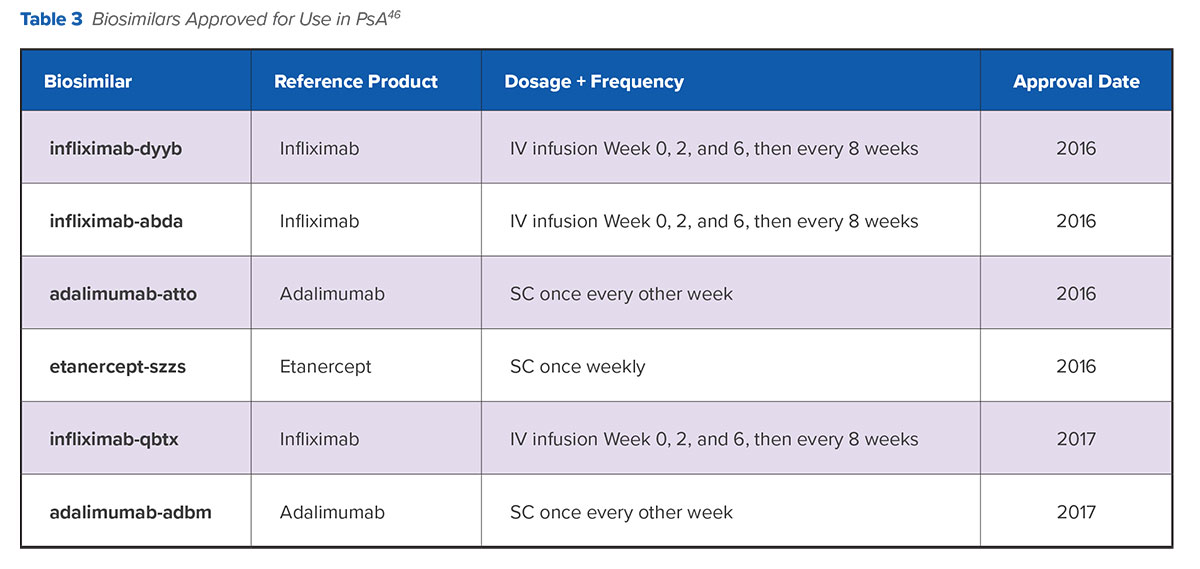

Patents for many biologic therapies have expired or are due to expire; therefore, several biosimilar versions of these agents have been developed or are currently in development. The FDA defines biosimilar products as large, complex molecules derived from biologic processes that are similar but not identical to the original agent.45 Biosimilar therapies are “highly similar” to their reference or originator products in physicochemical characteristics because they contain a version of the active substance (i.e., living cells) of a previously authorized, original biological medicinal product, known as the reference medicinal product or originator drug. As it relates to biosimilars, “drug switching” refers to exchanging a biologic agent with its own biosimilar to achieve the same therapeutic intent at lower cost.45 There are currently six biosimilar agents approved for use in PsA.

Biosimilars are likely to drive competition and accrue cost savings for payers and providers depending on setting and biologic class.47 Although there is considerable discussion in Europe about potential direct and indirect costs savings associated with greater biosimilar use, it is less clear what the estimated savings will be for patients in the United States since commercial insurance out-of-pocket costs for biosimilars are likely to be similar to biologics and might even be higher for patients enrolled in the self-administered Medicare Part D program.48-49

Biosimilar Use in Clinical Practice

Clinical and real-world data on switching from a reference product to a biosimilar are somewhat limited, but post-marketing observational and open-label extension studies on the use of infliximab in patients with RA and ankylosing spondylitis suggest that transitioning from the originator drug to the biosimilar results in neither efficacy loss nor an increase in adverse events or immunogenicity.51-52 A 2016 review of 53 switching studies across inflammatory diseases confirmed that there are few efficacy and safety differences between patients who switched from the originator drug to a biosimilar compared to patients who did not switch.53

More recently, the 52-week, randomized, double-blind, noninferiority, phase 4 NOR-SWITCH trial prospectively studied the process of transition from originator infliximab to its biosimilar (infliximab-dyyb) in patients with PsA, as well as RA, psoriasis, and other inflammatory diseases.54 The primary endpoints were worsening in disease-specific composite measures and/or agreement between the patient and investigator that increased disease activity required a change in treatment by week 52. Although the trial was insufficiently powered to compare treatment changes among patients within each disease category, the trial overall demonstrated noninferiority for its primary endpoints. Safety and immunogenicity were comparable between the treatment arms. The study findings suggest that patients with PsA can be switched from originator infliximab to its biosimilar without loss of benefit or intolerability.54

These accruing clinical data seem to support a switching strategy between reference drugs and biosimilars and could potentially build confidence among clinicians to switch their PsA patients to biosimilar agents if there are clear cost benefits. As of yet, these cost benefits are unclear. There is little data currently available on prescribing patterns for biosimilars in PsA or on patient receptivity to biosimilars in the United States. European prescribing data from the cross-sectional Adelphi Real World Biosimilars program suggest that many rheumatologists are still more likely to prescribe the reference product than the biosimilar for PsA patients, and a recent commercial survey of U.S. physicians who are members of a social network noted a similar trend.55 At the same time, studies suggest that patients with PsA are often reluctant to accept biosimilars on the basis of concerns about insufficient knowledge about biosimilars, potential side effects, and potential long-term problems.56-57 Both the ACR and the NPF currently suggest that switching a patient from an originator drug to a biosimilar should be done on a case-by-case basis and be discussed between patients and their providers.

Summary

Despite advances in therapeutics and the development of non-TNF inhibitors, challenges in the treatment of PsA point toward a need for efficacious new therapies with improved tolerability and long-term safety, as well as unique mechanisms of action that address multiple PsA clinical domains. Notably, since PsA patients with accompanying psoriasis frequently identify itch and pain as their most bothersome symptoms, therapies that promote more than 50% skin clearance should be a particular priority.5,22

Biosimilar agents are increasingly viewed as a cost-containing strategy in the management of chronic inflammatory conditions. However, there are, as yet, few signals that clinicians are willing to substitute biosimilar agents for their reference products. Consequently, the development of effective biological therapies beyond anti-TNF agents remains key, with several phase 3 trials likely to report pivotal trial results from 2020 onward. Given the high rates of response failure and the clinical challenges associated with switching therapies, broadening the PsA armamentarium is important for patients who fail current treatment options.