DROP THE ANCHOR? DMARD Monotherapy for the Treatment of RA

In order to complete this lesson, you must read the article provided. When you complete the article, scroll to the bottom to continue the course. You will receive your certificate after submitting the post-test and evaluation.

For years, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have formed the backbone of treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). While several different DMARDs may be used—including sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and hydroxychloroquine methotrexate (MTX) is the most commonly prescribed “anchor” drug.1 Across practice guidelines, MTX monotherapy is typically recommended as the initial treatment of choice in DMARD-naïve patients with RA, assuming the absence of contraindications to its use.2,3 This recommendation is based upon a wide body of literature supporting MTX as an effective, well-tolerated, and low-cost treatment option.1

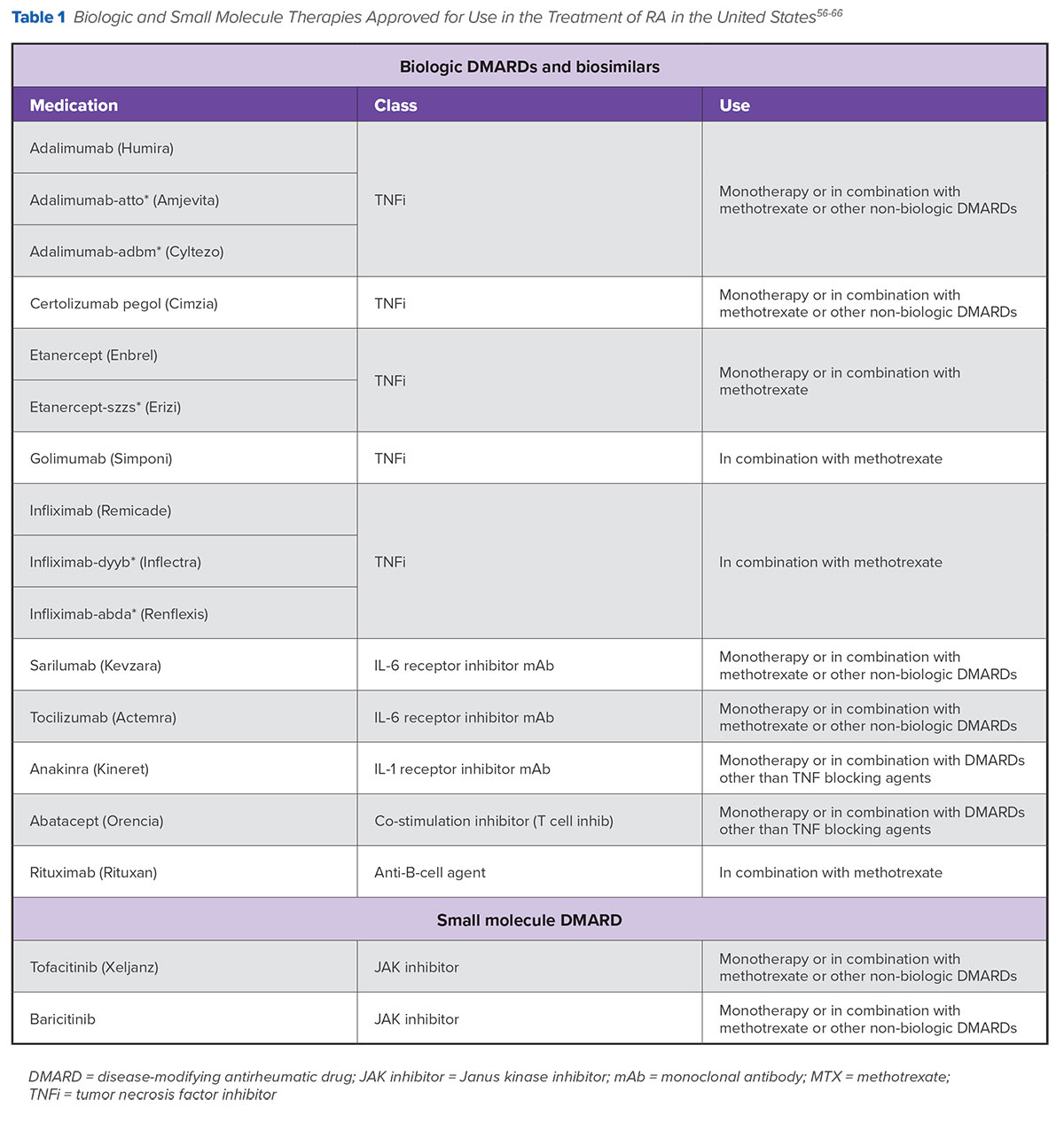

However, for a substantial number of patients, MTX monotherapy is not the optimal initial treatment approach for a variety of reasons, such as aggressive disease and family planning. For these patients, optimal initial treatment choices may include using MTX in combination with other agents as well as prescribing monotherapy with different medications.2 Over the last two decades, a number of new options, including injectable biologics, oral synthetic small molecules, and biosimilars, have become available to help clinicians and patients with RA attain clinical treatment goals, provide relief, and improve quality of life.3 In the United States, a number of these medications have been approved for use as both monotherapy and in combination with conventional DMARDs (Table 1 ).

A Look at Treatment Guidelines

The 2015 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline for the treatment of RA provides treatment recommendations as well as separate algorithms geared to patients with early (<6 months) and established (≥6 months) disease.2 In 2017, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) released its updated recommendations for the management of RA with synthetic DMARDs and biologics. In contrast to the ACR guidelines’ use of disease duration to stratify treatment pathways, the EULAR guidelines use the presence or absence of unfavorable prognostic factors.3

While there are some differences between the two, both guidelines are built around the guiding principles of achieving early disease control, utilizing a treat-to-target (T2T) approach, providing individualized care, and promoting shared decision-making. Each guideline provides treatment recommendations for when to introduce or switch to a new class of medication. Of course, it is important to note that these guidelines only provide recommendations and that the optimal treatment for an individual patient may differ from the option listed in the treatment algorithms.

Initial Therapy

Both the ACR and EULAR guidelines recommend DMARD monotherapy ± short-term, low-dose glucocorticoids (GCs) as the preferred initial therapy for most DMARD-naïve patients with RA. In the event MTX is contraindicated (or early intolerance is apparent), other DMARDs (eg, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and hydroxychloroquine) may be used. Based upon the T2T approach, therapy should be adjusted until the goal of clinical remission or low disease activity is reached. In the event that disease activity remains moderate or high despite optimized DMARD monotherapy (with or without GCs) or if patients develop side effects, intolerance, or adherence issues to MTX, additional treatment options should be considered.2,3

Subsequent Therapy

It is at this point that biologics and small molecules typically enter the picture. Treatment guidelines provide a variety of additional options and pathways, giving providers and patients the flexibility to individualize and optimize their care.

According to the ACR guidelines, recommended treatment options for patients with early RA who have moderate or high disease activity despite DMARD monotherapy (with or without GCs) expand to include the following:

- Combination conventional DMARDs

- Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor ± MTX

- Non-TNF biologic (ie, rituximab, abatacept, sariliumab, tocilizumab, anakinra) ± MTX

For patients with established disease, tofacitinib ± MTX is a treatment option in addition to the above choices. Short-term, low-dose GCs may also be added to any treatment regimen.2

In contrast, EULAR treatment recommendations for patients who do not achieve improvement or experience side effects with initial DMARD monotherapy are stratified by the presence or absence of unfavorable prognostic factors such as moderate to high disease activity following DMARD therapy, high swollen joint counts, and/or high levels of acute phase reactants. For those patients without unfavorable prognostic factors, treatment includes switching to or adding another conventional DMARD, preferably with the addition of short-term GCs. For patients with unfavorable prognostic factors, EULAR guidelines recommend combination therapy by adding a biologic or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor such as tofacitinib or baricitinib (approved in Europe for several years but only recently approved in the United States) to the existing DMARD.3

When selecting a biologic or small molecule, consideration should be given to factors such as cost, comorbidities, contraindications, side effect profile, and burden of taking the medication.2,4 Neither ACR nor EULAR guidelines provide recommendations for individual medications within a medication class, and both indicate that all biologics may be used without hierarchal positioning.

Due to the availability of long-term registry data, biologics are given slight preference over JAK inhibitors.2,3 Biosimilars, if available, may be used as a substitution for originator biologics.3

Depending on treatment response, further treatment options include optimizing the dose of a biologic, cycling to another medication with the same mechanism of action (MOA), or switching to a medication with a different MOA.2-5

Is Initial Biologic or Small MoleculeMonotherapy Ever Appropriate?

At this time, neither guideline recommends biologic monotherapy as first-line therapy over DMARD monotherapy.2,3 While some studies have shown that early biologic monotherapy is superior to MTX monotherapy, none of these studies used GCs in combination with MTX. Furthermore, other studies comparing a biologic + MTX against MTX + GCs have not demonstrated a clear clinical or structural advantage of early biologics in the frontline setting. Thus, there is a lack of compelling evidence for this strategy compared with MTX + GC as first-line therapy.

In terms of treatment approaches after initial DMARD failure, the ACR guidelines provide flexibility for biologics (TNFi, non-TNF biologics) and tofacitinib to be used with or without MTX; however, they do note the superior efficacy of combination therapy.2 In comparison, the EULAR guidelines recommend that biologics and JAK inhibitors be used in conjunction with a conventional DMARD. These recommendations reflect data showing that most biologics and small molecules combined with MTX demonstrate superior efficacy compared with respective monotherapy.2,3

In the event combination therapy with a conventional DMARD is not an option, the EULAR guidelines suggest monotherapy with either an interleukin (IL)-6 pathway inhibitor such as tocilizumab or tofacitinib.3 This is based upon data indicating tocilizumab and tofacitinib monotherapy exhibit somewhat better efficacy compared with MTX monotherapy. Monotherapy with other biologics, meanwhile, has not been found to be clinically superior to MTX monotherapy.3,6

Real-World Use of Biologic and Small Molecule Monotherapy

While expert guidelines generally don’t recommend biologic monotherapy for patients with RA, studies suggest that monotherapy regimens are popular in real-life clinical practice.7-9 Data derived from 2 analyses of Medicare plans in the early biologic era (1999-2005 and 2006-2009) indicate that more than 25% of patients with RA have a biologic incorporated into their treatment plan; of those, nearly one-third who initiated or switched to a biologic received it as monotherapy. Consistent with guideline recommendations, the vast majority of these patients (>85%) had been treated with a conventional DMARD prior to receipt of their first biologic, usually MTX.8,9

Similar results were reported in a more recent analysis of patient data in the CORRONA registry. Between 2001 and 2012, amongst biologic-naïve patients with RA who initiated therapy with a biologic agent, 19.1% initiated the biologic (most commonly an anti-TNF) as monotherapy. The vast majority (95%) of patients had received treatment with a conventional DMARD, most commonly MTX, prior to biologic initiation. The most common reasons for discontinuing any prior DMARD and initiating biologic monotherapy were unacceptable toxicity, lack of efficacy, and physician preference.7

Pathways to Monotherapy withBiologics and Small Molecules

Patients taking biologics and small molecules as monotherapy may arrive to that point via several different pathways. Some patients never initiate MTX monotherapy (or another conventional DMARD), while others discontinue MTX monotherapy for a number of reasons.

Examples of patients who typically never initiate treatment with MTX include those with a contraindication to MTX such as pregnant or breastfeeding women; alcohol users or patients with liver disease; pre-existing blood dyscrasias; known hypersensitivity; lung disease; chronic/acute infection; significantly impaired hepatic and/or renal function; and/or other comorbidities. MTX is also subject to a number of drug-drug interactions; consequently, caution is warranted with its use in elderly patients due to the renal excretion of MTX.11,12

Patients that do start MTX monotherapy may discontinue treatment due to drug-induced intolerance/adverse events or patient/physician preference.

While many RA patients experience mild or moderate side effects while taking MTX, the drug has a long history of generally favorable long-term safety. MTX is associated with a relatively low treatment discontinuation rate of 16% due to adverse events.1,14 Intolerance to MTX can involve physical symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fatigue) that become anticipatory or associated with MTX intake as well as behavioral symptoms (e.g., irritability, crying, drug refusal). Intolerance may also contribute to reduced adherence to therapy.15

Some data suggest that patients who experience an inadequate response or develop intolerable adverse events to oral MTX may benefit from switching to the subcutaneous version of the drug. Taken at the same dosage as the oral formulation, subcutaneous MTX has been associated with greater clinical response as well as improved gastrointestinal tolerability compared with oral MTX.16,17

Other patients may decline or discontinue treatment with MTX due to personal preference. For example, some patients may not want to abstain from alcohol, while other patients may decide MTX is the wrong treatment choice due to family planning decisions or not wishing to use effective contraceptives during the treatment course.12

When Is It Appropriate toPrescribe Biologic or SmallMolecule Monotherapy?

As mentioned earlier, neither the ACR nor EULAR guideline recommends prescribing biologic or small molecule monotherapy over conventional DMARD monotherapy as first-line treatment for most DMARD-naïve patients, and both indicate biologic and small molecule therapies are best used later in the treatment landscape in combination with MTX or another conventional DMARD, when possible.2,3

However, treatment recommendations do not necessarily preclude the decision to use biologic or small molecule monotherapy as part of an individualized treatment approach. For some patients, including MTX or another conventional DMARD into the treatment regimen may not be appropriate for a multitude of reasons (see Table 2). For these patients, initiating or switching to monotherapy with a biologic or small molecule may provide clinical benefit, improve adherence, and help patients reach treatment goals.

Biologic or Small Molecule Monotherapy: WhatDoes the Data Say?

For a substantial number of patients with RA, it is highly likely they will receive treatment with a biologic or small molecule, either as monotherapy or in combination with MTX or another conventional DMARD, at some point during their disease course.

Unfortunately, extrapolating data from clinical studies and applying it to clinical practice is complicated because head-to-head comparative data is limited, and available information is often the result of indirect comparative studies, meta-analyses, and systematic literature reviews. This section will discuss some of the overall efficacy and safety trends observed with biologic and small molecule therapies.

While numerous studies have been conducted evaluating biologics and small molecules as monotherapy or in combination with MTX/DMARDs against MTX/other DMARD monotherapy and/or placebo, substantially fewer studies have directly compared the safety and efficacy of biologic or small molecule monotherapy against itself in combination with MTX/other conventional DMARD. This section, while not exhaustive, will highlight examples of clinical trials in which the safety and efficacy of biologic or small molecule monotherapy was compared with itself in combination with MTX/other conventional DMARD (Table 3).

Overall Efficacy

Based upon the literature, several overarching themes regarding the use of biologics and small molecules can be made, including the following:3,6,18-34

- At this time, it is still not clear if there is an optimal choice or sequence of biologic and/or small molecule therapies following failure of MTX monotherapy

- Biologics and small molecules have demonstrated improved clinical efficacy when used in combination with MTX compared with MTX monotherapy

- Biologics and small molecules have improved efficacy when used in combination with MTX compared with monotherapy

- If combination therapy is not feasible, the literature supports the use of tocilizumab or tofacitinib monotherapy over other biologics as they have demonstrated better efficacy compared with MTX monotherapy

The greater efficacy of tocilizumab monotherapy compared with MTX was established in the AMBITION study. Patients with active RA for whom previous treatment with a DMARD/biologic had not failed were assigned to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg every 4 weeks or MTX 7.5 mg/week titrated to 20 mg/week.

At week 24, tocilizumab monotherapy demonstrated superior efficacy, with 69.9% of patients achieving an ACR20 response compared with 52.5% in the MTX treatment group. The incidence of severe adverse events and serious infections was similar between the 2 groups, occurring in 3.8% vs. 2.8% and 1.4% vs 0.7% of patients in the tocilizumab and MTX arms, respectively.28

Results from the 52-week SURPRISE study also support the use of tocilizumab monotherapy. In this study, patients with RA and moderate or high disease activity despite MTX were assigned to receive tocilizumab either as an add-on to MTX or as monotherapy. In this study, tocilizumab monotherapy was found to be superior to MTX/DMARD monotherapy. However, it should be noted that tocilizumab used in combination with MTX led to more rapid suppression of inflammation and reduction in radiographic progression compared with switching from MTX to tocilizumab monotherapy.29

Similarly, the greater efficacy of tofacitinib compared with MTX was established in the ORAL START trial. In this study, patients with moderate-to-severe RA who had not received MTX or were not receiving therapeutic doses of MTX were assigned to receive either 5 mg or 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily or MTX (titrated to 20 mg/week). At month 6, 25.5% of patients in the 5 mg tofacitinib group and 37.7% in the 10 mg tofacitinib group had achieved an ACR70 response compared with 12.0% of patients in the MTX group. Infections and gastrointestinal disorders were the most common adverse events across all 3 treatments arms. Broadly speaking, MTX tended to be associated with more gastrointestinal side effects whereas tofacitinib appeared to be associated with more infections. Four percent (4.0%) of patients in the combined tofacitinib arm developed herpes zoster compared with 1.1% in the MTX arm. The incidence of bronchitis and influenza were also higher in the combined tofacitinib arms (6.1% and 2.8%, respectively) compared with MTX (2.2% and 1.6%, respectively). In the tofacitinib arm, 5 cases of cancer developed compared with 1 in the MTX arm. The incidence of severe adverse events and serious infections was similar between the 5 mg, 10 mg, and MTX arms, occurring in 10.7% vs. 10.8% vs 11.8% and 3.0% vs. 2.0% vs 2.7% of patients, respectively.35

Data suggest that the JAK inhibitor baricitinib, which recently received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration at a 2 mg dose, may be more efficacious compared with TNFi in patients who have had an inadequate response to MTX.36

Overall Safety

The overall safety of biologics, including TNFi and non-TNFi agents, was compared with conventional DMARDs in a recent review article. Patients receiving any biologic were at an increased risk of serious infection (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 1.1 to 1.8) and tuberculosis (HR: 2.7 to 12.5), but not herpes zoster infection. Overall, patients on biologic therapy were not at increased risk for malignancies in general, lymphoma, or non-melanoma skin cancer. The risk of melanoma was found to be slightly increased (HR: 1.5), although that was based on the results of only one study. Interestingly, the rate of serious infection on biologic therapies was lower in more recent trials compared with older studies, possibly reflecting improved screening and management of patients at risk for infection.37

Similarly, the overall safety of small molecules, as monotherapy and in combination with MTX, was also evaluated in a recent review. With tofacitinib, the most commonly reported laboratory abnormalities included mild decreases in lymphocyte and neutrophil counts, and mild increases in aminotransferase and creatinine levels. Baricitinib, meanwhile, was associated with reduced hemoglobin levels. Compared with placebo, the relative risks for serious AEs with tofacitinib and baricitinib were 0.8 and 1.0, respectively. However, tofacitinib was associated with a significantly increased risk of herpes infection.31

Adherence/Persistence to Biologics and Small Molecules

Overall, an estimated one-third of patients discontinue therapy with their first biologic within a year of the initiation of treatment. This can occur for several reasons, including primary ineffectiveness, loss of efficacy over time, or drug intolerance.4 One series of real-world data found patient persistence—defined as continuing with an initial biologic without switching to another biologic and without a gap in therapy of 45 days or longer—at 1 year after initiating biologic therapy with etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, or abatacept of 45.7%, 42.9%, 40.8%, and 40.5%, respectively. Across these treatment groups, on average, 34% of patients discontinued biologic therapy, 18% restarted therapy with the same biologic, and 6% switched to a different biologic.10 A provider survey of rheumatologists found the vast majority of patients typically cycle through 2 to 3 different biologics during their disease course.38 Other factors may influence treatment adherence and persistence as well, such as patient preferences, beliefs, and cost.

When looking at factors that may influence treatment adherence/persistence, a study assessing patient preferences for second-line therapy (biologic or small molecule) found that patients highly valued an oral treatment option that didn’t need to be combined with MTX. Medications requiring IV infusion were the most strongly opposed treatment option. Interestingly, in terms of frequency of administration, patients strongly preferred twice daily intake over intake every 1-2 weeks.39 Other data has confirmed that patients state a preference for oral treatment options.40

Patient beliefs and experiences with biologic therapy have also been shown to influence adherence. A longitudinal study assessing adherence to adalimumab therapy found that approximately 25% of patients reported low to moderate adherence to therapy. Factors positively associated with increased adherence included increased belief in medication necessity, lower concerns about medication use, increased treatment control, strong views of chronicity of RA, and increased professional and family support.41

Lastly, the cost of treatment has also been found to influence treatment adherence/persistence. An analysis of patients enrolled in the Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug plan (N=864) found member out-of-pocket (OOP) costs significantly affected treatment initiation and adherence to biologic therapy. Overall, 18.2% of patients (157/864) had no evidence of filling initial biologic prescriptions (initial prescription abandonment). The rate of initial prescription abandonment varied with OOP costs. For example, of the 265 patients in the $0-25 OOP cost group, no patients had evidence of an abandoned biologic prescription. In contrast, initial abandonment occurred in 32.7% of patients (54/165) in the >$550 OOP cost group. Similar trends were observed for the likelihood of refilling a prescription for a biologic.42

Although real-world evidence evaluating small molecule persistence/adherence is scarce, a retrospective analysis comparing real-world adherence/persistence for tofacitinib vs. biologics over a 12-month period (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) found persistence/adherence between the two was similar.43

The Role of MTX in the Formation of Antidrug Antibodies & Cardiovascular Health

Beyond improved clinical response, there are several other reasons to consider using MTX as part of a treatment plan when treating patients with biologics and small molecules. These include possible mitigation of the formation of antidrug antibodies as well as cardiovascular protective effects of MTX.

One of the concerns about the use of biologics is the potential loss of efficacy due to the formation of antidrug antibodies. Antidrug antibodies can form as a result of the body’s production of an immune response to biologic therapy if it is seen as a foreign invader. Antidrug antibodies can bind and neutralize biological agents, dramatically reducing the concentration of active, unbound drug molecules in the blood.44

While the formation of antidrug antibodies is a phenomenon universal to all biologic agents, it appears to be especially common with TNFi drugs. Up to 30% of patients fail to respond to TNFi therapy, and 60% of patients who initially respond to TNFi therapy subsequently experience loss of efficacy.44,45 Antidrug antibodies are believed to play a role in this, with findings in the literature indicating the formation of antidrug antibodies in response to TNFi therapy correlates with decreased functional drug levels, loss of therapeutic response, and/or adverse events such as infusion reactions.46-49

A study evaluating the development of antidrug antibodies in patients with RA treated with adalimumab—either with concomitant DMARD or as monotherapy—found that 28% of patients developed antidrug antibodies over a 3-year treatment period. The incidence of antidrug antibody development was substantially higher in patients not receiving concomitant DMARD therapy. The development of anti-adalimumab antibodies was associated with lower serum adalimumab levels, reduced clinical response, and higher rates of treatment discontinuation.50

The picture is less clear for non-TNFi agents. The ACT-RAY study compared the number of patients who developed antidrug antibodies while receiving tocilizumab as an add-on to MTX or as part of a switch to monotherapy. At 1 year, the number of patients with antidrug antibodies was comparable between the two groups (1.5% and 2.2%, respectively), with overall data suggesting the immunogenicity of tocilizumab may be lower compared with other biologics.51 Findings from the literature suggest that MTX, given even at low doses (7.5-10 mg/kg), is generally well tolerated and has been associated with reduced formation of antidrug antibodies as well as improving the efficacy of biologic therapy, further supporting its role in combination therapy.3,44

It is widely accepted that individuals with RA are at increased risk of cardiovascular events compared with the general population.52 Evidence in the literature has found that MTX and other conventional DMARDs are associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular events.18,53 A recent review of 28 studies found that MTX was associated with a reduced risk of all cardiovascular events in patients with RA.53 Reductions in risk of acute myocardial infarction (MI) have also been observed in real-world practice. A large retrospective study of 107,908 commercially insured patients taking any DMARD for RA found the current use of any DMARD was significantly associated with reduced risk of acute MI.54 These findings suggest MTX and other DMARDs may serve an important role in providing cardioprotective effects in the treatment of patients with RA.

Approaches to Tapering Biologic Treatment

With current therapies and the T2T strategy, longterm remission is now achievable in more than 50% of patients with RA.55 When patients achieve long-term remission with biologic therapies, issues such as potential overtreatment, long-term adverse effects, economics of therapy, and patient preferences enter the conversation.55

So what guidance is available for patients who achieve treatment targets of either low disease activity or clinical remission when on combination therapy? The ACR and EULAR treatment guidelines both address the issue of drug tapering and recommend that tapering only be considered for patients with sustained remission on current therapy (see Figure 2 ). The suggested order of tapering is GCs, followed by biologics, especially if used in combination with conventional DMARDs.3 While factors such as disease duration, degree of improvement, and duration of remission may help guide tapering decisions, more research in this area is needed.3,19

When tapering is discussed, it is usually done so in the context of dose reduction or increases in intervals between drug administration.3 Evidence supports that most patients receiving therapy with a biologic + MTX can reduce the dose of their biologic by up to 50% or increase the interval between doses accordingly and maintain their low disease activity, with little risk of flares.19 However, the possibility of flares should be discussed when exploring the option of tapering, and a plan should be developed for monitoring and managing a flare in the event one occurs that reflects patient values and preferences.2

It is important to note that drug tapering is different than drug discontinuation, which in the case of a biologic therapy often leads to disease flares.19 However, even in the event of disease flares following tapering or discontinuation, most patients will recover their previous treatment response on intensification or reinstitution of therapy.3 EULAR guidelines reflect the view that patients with RA on conventional DMARD monotherapy, even if they have achieved sustained remission, should never fully stop treatment.3

Summary

As the number of treatment options has expanded for the treatment of RA, determining optimal therapeutic approaches has become increasingly complex. Clinical practice guidelines that are based upon currently available data provide support to rheumatology providers for treatment approaches. However, it is ultimately up to rheumatology providers to determine when to implement, change, or taper RA therapies, as well as decide which agents to use. This process reflects assessing the risk/benefit of various monotherapies or combination therapies based on efficacy and safety data, and balanced with patient treatment goals, values, and preferences.